|

| Family Trees -> Barth Dunham Fitz Randolph Freeman Giles Ilsley Jackson Luthin Venable Waldershelf Wilson |

|

| Family Trees -> Barth Dunham Fitz Randolph Freeman Giles Ilsley Jackson Luthin Venable Waldershelf Wilson |

Jonathan Dunham alias Singletary and Mary Bloomfield are born just two days shy of two years apart. During their childhood, he lives in Salisbury and Haverhill and she in Newbury, of Essex County, Massachusetts. This is likely where he learns something of construction and milling as there is considerable mill construction and operation along the rivers there. At the age of 19 and 17, respectively, he and Mary start their family in Haverhill with Esther and Mary. They move briefly to Connecticut where they have two more girls, Ruth and Eunice, and where he may have built a house and mill. Upon their move to Woodbridge, New Jersey, he builds the house and mill for which he is known, serves as town clerk, and has some of his more controversial exploits. It is in Woodbridge that their four boys are born - Jonathan, David, Nathaniel, and Benjamin. Mary dies there in 1705 at age 63 and he in 1724 at age 84, survived by just three of their eight children.

To me, he seems the embodiment of the American character. At various times throughout the many decades of his life he demonstrates courage, faith, fortitude, loyalty, industriousness, perseverance, and determined independence. Yet he is but one representative of the ingenious, self-reliant yeomen, women, and their children that made colonial America the birthplace of a great democracy. He is also someone several puritans, researchers, historians, and genealogists have most unfairly characterized. I trust an objective review of the documentation offered helps to set the record straight on the extraordinary and exemplary character of this individual.

For a possible explanation of his name change to Dunham alias Singletary, please see the discussion on the origins of Jonathan's father, Richard Singletary.

Select a title below to explore some of the events and controversial episodes of his full life or open all sections and browse.

There is something reaffirming about Mr. Parker's sermon the day Goodwife Singletary is laid to rest. Or perhaps it was just the end of a long winter with an ailing wife. Whatever the reasons, the widower, Richard of Newbury, develops a new sense of hope for the future. The grieving 50 year old finds affection has grown between him and Susanna Cooke. Perhaps she admires his love for his wife. Maybe, at the age of just 24, she is attracted to his yet youthful and rugged good looks, his caring manner, or the wisdom she found in his eyes. Perhaps she feels he would be a good husband and father.

It would have been that Spring of 1639 that their first son, Jonathan, is conceived. That year, they resolve to marry. It would be difficult to imagine they did not marry. Yet there is no record of their marriage to ascertain the event or date. With a number of other Newbury residents they move north across the Merrimac to Salisbury, where he becomes a proprietor (Pope, p.416). He may also keep his plot on Deer Island in that majestic river that divides the two townships.

In January, 1640, Jonathan is born to Susanna and Richard (MA-VR), perhaps in a house they share with another family of Salisbury; perhaps before they remove from Newbury. That Jonathan is the son of Richard and Susanna (rather than Goodwife Singletary) is confirmed by a 1702 deed that references that fact. (CoM, p. 202.1-203.1) It is sometime in 1639 or 1640 that Richard, among a dozen others, acquires land there (Merrill, p.11) so as to build his own home for his new family.

This structure is built with more enthusiasm and a renewed hope for the future. After house lots are laid out, planting land is assigned. In many cases house lots and planting lots are located near each other for safety from sudden Indian attack. In one of the divisions, around the outside of the semi-circular road that runs from the north at what would now seem to be Rocky Hill Road to the cemetery and beach road on the south. It is in this division that Richard’s name appears. (Merrill. p.12)

In August, Jonathan is just 7 months of age and not yet walking or talking. Perhaps the young mother, Susanna, carries him about town on pleasant summer days to pass the time with neighbors. As they pass the Spencer farm this day they happen upon William Osgood and some others from town who are building a barn for Mr. Spencer. Richard may have been among that party. They are just finishing the frame and breaking for a midday repast when John Godfrey has a curious exchange with Goodman Osgood.

Susanna greets the crew foreman, "Good day, Mr. Osborne! How are you and your wife Elizabeth?" She exchanges a wave of the hand with her husband Richard, as well.

"Good day to you, Mrs. Singletary. We are very well, thank you," replied William. "And how is your fine and joyful son this morn?" Osgood is a rugged individual, with his white, linen sleeves rolled up to his elbow and just a bit of sweat glistening on his tanned brow.

"He is healthy and strong as the timber of your stout frame, good sir," said Susanna.

John had been tending to Mr. Spencer's cows when he notices the workmen break for food and as eager to share news with Mr. Osgood.

"Good day," said William and Susanna simultaneously.

"It is a fine morning, it is," exclaims Godfrey with an inextinguishably broad smile upon his impish face. He is a bit disheveled in his gray flannel pants, white shirt and vest, too warm for a mid-August sun. His curly, red hair bore bits of dry grass from the ground he had been lying upon.

"And how’s this chubby child?" as he tweaks the babe's rosy cheek.

As Jonathan begins to cry, Susanna reflexively pulls him back.

"He does well, sir. Fussing is not his usual way," replies the startled mother. "I believe it is time for us to move on. I am yet to see Mrs. Woodbridge about some sewing she has. Good day to you, Mr. Osgood. Good day to you," she said pausing to examine Godfrey just a bit longer. She then takes a brisk pace, swinging Jonathan gently as she strides over to Richard.

Godfrey turns quickly to engage Mr. Osgood in a conversation that William will recall in a court affidavit 18 years later. (Upham, v.2 p.432)

"I’ll soon be done keeping cows as I've gotten a new master," said Godfrey with apparent pleasure.

William asked of him, "Who would that be?"

"I know not," answered Godfrey.

Osgood asked him, "Where does he dwell then?"

Godfrey answered, "I know not."

Osgood asked again, "Then by what name is he known?"

Godfrey answered, "He did not tell me."

Osgood then said to him, "How, then, wilts thou go to him when thy time with Mr. Spencer is out?"

Godfrey said, "The man will come and fetch me then."

Osgood asked him, "Hast thou made an absolute bargain?"

Godfrey answered that a covenant was made, and he had set his hand to it. Osgood then asked of him whether he had not a counter covenant.

Godfrey answered, "No."

William, quite puzzled, exclaimed, "What a mad fellow art thou to make a covenant in this manner!"

Godfrey said, "He's an honest man."

"How knowest thou?" said William, at a loss.

Godfrey returned, "He looks like one."

"I am persuaded thou hast made a covenant with the Devil," William concluded.

Godfrey skipped off proclaiming, "I profess, I profess!"

Osgood is not perplexed so much by Godfrey's excitement at prospective employment as he is surprised with his ignorance of his new master and duties. Perhaps herding cows isn't paying as well as it had. There are plenty of cattle to be tended in those days with estimates of 12,000 in the colony. However the price falls by 80 percent as emigration from Europe abruptly declines and there is no transportation of goods in return. (Coffin, p.32)

The economic impact of the reduction in trade is deep, wide, and long. Hard currency becomes so scarce that Winthrop's government sets fixed equivalences of commodities in place of coin since neither "money nor beaver" are to be had. Indian corn becomes worth four shillings, rye is set at five shillings, and wheat at six shillings in payment of all new debts. "Men could not pay their debts though they had enough. He that three months before was worth 1,000 pounds could not raise 200 hundred pounds even if he sold his whole estate." Governor Winthrop laments the "notorious evil" of the common practice to buy low and sell high. (Coffin, p.32)

It seems that Jonathan is born at the advent of the first economic depression of the North American continent. During 1640, the prominent Reverend John Woodbridge is fined two shillings and sixpence for release of a servant. In May, several Newbury inhabitants find it necessary to try their prospects elsewhere and petition the Winthrop government to allow their resettlement in Pentucket (now Haverhill) and Cochichawick (now Andover). So many others in the colony remove to foreign locations that there is a net loss of inhabitants. Yet some, such as Mr. Richard Dummer, have such reserves as to contribute as much as one-fifth of the ₤500 in total voluntary contributions to the government raised that month by the several towns. Dummer’s sum being more than half that of all of Newbury. Is it benevolence or, in effect, protection money against suffering under the authoritarian views of "Winthrop and other triumphant sound religionists" that rule the colony with fines, lashes, imprisonment, and banishment? (Coffin, p.33)

Religion is the basis for the first efforts to educate the young with a general court order in 1641 that town elders prepare a "catechism for the instruction of youth in the grounds of religion." To wit, James Noyes, teacher of the Church of Christ in Newbury, drafts a “short catechism” of 99 questions and answers to be recited as evidence of education in such matters. I note that it includes mainly propositions to support the authority of the Church based on select passages from books such as Acts and John. (Coffin, p.287)

Court cases of Essex County in the 1640's are filled with trespass of one against another; debt, slander, blasphemies, trespass, drunkenness – both public and private, and failure to observe the Sabbath in various ways. (Dow, v.I p.42 and beyond) Sadly the 99 questions include not one mention of forgiveness or the Golden Rule, let alone teaching a man to fish. It’s a pity Mr. Noyes does not go for 100 – such is their first effort toward “instruction.” Perhaps then the Puritan authorities would more quickly realize the hypocrisy and sin of the savage punishments they exact upon their fellow man and, especially, women in the name of their God.

Richard spends much of the next several years tending his crops on Deer Island and, perhaps, helping build structures for others in return for commodities he does not produce or money when available. This is necessary to support a growing family, as Eunice is born January 7, 1642 (MA-VR); Nathaniel on October 28, 1644 (MA-VR); and Lydia on April 30, 1648. (MA-VR)

During the spring of 1642, there is much debate regarding property rights and even the location of the town center and its meeting house. Rules for the acquisition of new land, establishment of areas for the common use and other issues of resettlement are decided by the town as a whole. In particular, it is hard for those that contributed to the building of the first meeting house give up that investment toward the building of a new structure three miles to the north. (Coffin & Bartlett, p.36) Discussion around the dinner table likely reflects the issues presented at meeting.

Meanwhile, young Jonathan probably helps his mother with the house, maybe tends a garden plot in the yard, collects firewoood, or plays with neighbor children that accompany their mothers visiting Susanna. Neighbors are nearer each other than in Newbury and visits are a frequent pastime. Later in these early years he accompanies his parents to church service and then school to learn the catechism.

July 5, 1643, there is a great wind (a tornado) that "fell multitudes of trees" and lifts the Newbury meeting house off its foundation with people in it. (Coffin & Bartlett, p.39) It cuts a 33 mile path straight from Lynn, Massachusetts to Hampton, New Hampshire, passing through Newbury and the eastern plains of Salisbury. Perhaps this is the inspiration for what is now US Route 1. Miraculously, only one person is killed - an Indian hit by a falling tree. It should have also settled the debate on the fate of the first meeting house, but does not. Surely, the people of the area have reason to give thanks to their Maker and Protector for their salvation from such great and sudden destruction.

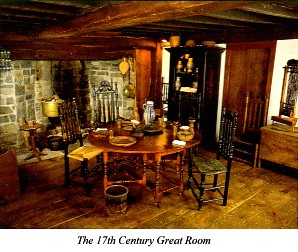

At dinners after Richard returns from the field or helping build a barn, house, or shed, news of the day is exchanged among them. An autumn supper of corned or boiled beef, root vegetables, and corn bread might likely be served by Susanna - with Jonathan’s help clearing the table of the day’s housework to make room for their plates. The meal is cooked in pots on the hearth in the one great room, dished onto plates, and passed to Richard at the table but a few feet away.

Perhaps it is such an autumn occasion at the table in front a warming blaze that Richard tells the family he has been engaged to help construct the foundation for a second grist mill near the mouth of the Powow River. He explains that William Osgood builds and operates mills for the grinding of meal or cutting of lumber."

Richard might explain how the masonry has to be very solid; strong enough to withstand the rumbling vibrations of operation; stronger than the shaking of an earthquake and the great winds - both recently felt in these parts. It is a great enterprise of many men, animals, and wagons; bringing rocks from the river’s edge, trees to Osgood’s lumber mill, and cut boards and beams for the use of many carpenters. At a yet tender age, this may be Jonathan’s first impression of the kind of engineering skill needed to build a mill.

"Father, can I come with you sometime?" begs Jonathan looking most eager and inquisitive.

Richard passes glances with Susanna, noting her approving grin. "If your mother can spare you, son, then you may visit on some occasion," Richard confirms in a fatherly tone.

Jonathan stares nervously at his mother as she nods her affirmative response.

"Oh!" exclaims Jonathan. "I can hardly wait."

"Maybe tomorrow we will take our poles to the spot. I’ll bet there’s some good fishing there," suggests Richard.

"Oh, that would be wonderful!" Jonathan replies enthusiastically.

"Let us not be too excited yet, Jonathan. It is time you are off to slumber and be rested for your adventure," interjects Susanna. "I’ll be expecting some fine catch for the morrow's supper." Eunice and Nathaniel are already snoozing on their blankets on the floor by the warmth of the fire.

The next day is the first of many for Jonathan to explore further from home, sometimes to help his father in the fields or watch him build something from a safe distance, likely ready with the questions at every opportunity. Later he may venture more on his own and with friends his age, as his younger siblings take his place by their mother’s side. Certainly he and his friends would gather together before and after school that commenced in such substantially sized towns following a county order in 1647 that requires the teaching of reading and writing so that the “ould deluder, Satan,” can not keep men from the knowledge of the Scriptures. (Merrill, p.36)

The years 1646 and 1647 are accompanied by considerable hardship and contention among the populations of the plantations. In 1646, both Salisbury and Newbury struggle over proposals that would split their populations. Salisbury's debate is a matter of convenience in church attendance as they find their population expanding and themselves separated by the Powow River (Merrill, p.35); while Newbury’s debate is the contention over relocating the meeting house that lasted until 1672. Meanwhile, a plague of caterpillars overtakes the meadows and crops of the several plantations in June of 1646 (Coffin & Bartlett, p.46), yielding a shortage of corn by the following spring. Coincidentally, there is also a great epidemic among all the population, god-fearing European and Native Indian, alike. (Coffin & Bartlett, p.48)

As the historian Deetz puts it, "underlying and permeating the approach of seventeenth-century English colonists to the political and social worlds they lived in was a deeply rooted folk tradition of superstition and belief in the supernatural, which existed alongside their religious faith." They search for explanations for the good and bad of everyday life and find God or the Devil, as the preachers of the day, notably Increase and Cotton Mather, teach intolerance of anything not in obedience to their world view. (Deetz, p.86)

If crop failures, great winds, and sudden death and destruction could be considered the work of God, it is surely to smite them for their ungodly behavior of drunkenness, promiscuity, brazen dress, or failure to display their faith by attendance at weekly meetings to hear these beliefs reinforced from the pulpit. Is it any coincidence, then, that the first trial and execution for witchcraft in New England occurs May 1667 in Hartford, Connecticut, with the hanging of the woman Alse Young of Windsor? (Love, p.283) Surely, these events are topics of discussion throughout the meeting houses, churches, and homes of the country. And this is but the beginning of a 50-year trend.

A Sketch of the History of Newbury, Newburyport, and West Newbury, Joshua Coffin and Joseph Bartlett, 1845.

History of Amesbury, Joseph Merrill, 1880.

Old Families of Salisbury and Amesbury, David W. Hoyt, 1889.

Pioneers of Massachusetts, Charles Henry Pope, Heritage Books, 1900.

The Colonial History of Hartford, William DeLoss Love, 1914.

Records and Files of the Quarterly Court of Essex County, Massachusetts, Volumes 1-4, Massachusetts County Court (Essex County), George Francis Dow, Massachusetts. Inferior Court (Essex County), Essex Institute, 1921.

Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Benjamin Ray, The Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia, 2002.

Salem Witchcraft, Volumes I and II, Charles Upham, 1969.

Vital Records of Salisbury to the End of the year 1849 – Volume I, Births, Topsfield Historical Society, Topsfield, Massachusetts, 1915.

The Times of Their Lives, James Deetz and Patricia Scott Deetz, 2000.

By 1650, Richard acquires a house lot in Haverhill valued at £60. (Chase, p.72) Mirick and Whittier find him with 22 others listed as settlers there as early as 1646, but there is some question as to the validity of that date. Since Amos Singletary is born to Richard and Susanna at Salisbury in April, 1651, perhaps Richard spends some time clearing timber from a farming lot and/or building a larger house to accommodate their growing family. (Chase, p.72) The house is likely of one story. A second story is often one large room for the children. The more elaborate houses likely have a shingle roof while one story cottages often have a thatched roof. Before 1700, houses often have one large fireplace, with a hearth expansive and tall enough to accommodate bench seating (called "settles") that offers a view of the sky up the chimney to anyone "settled in" there. (Chase, p.95) It is not hard to imagine the 10 year old Jonathan lending a small hand to get tools and such while learning more about construction. The family then moves the 13 miles up the Merrimac River to Haverhill later that year.

In Haverhill, bees are introduced by Thomas Whittier a few years earlier and honey, therefore available. (Chase, p.67) Beneficial to all, is the planting of two orchards about this time by Stephen Kent and John Clements. (Mirick & Whittier, p.33) The fruit trees need the bees and yet will not produce flowers and fruit of any quantity for some years to come. Clay pits are established for use in making both brick and mortar. (Mirick & Whittier, p.33) John Hoitt, brick maker, is induced to move here from Ipswich at this time with a grant of land and the use of these pits. (Chase, p.71) The only source of lime for construction is derived from clam shells as limestone is not quarried there as yet. (Chase, p.83) Until then, logs and lumber siding on buildings are sealed or daubed with the less durable clay giving the term clay-board or clapboard siding its meaning. (Chase, p.95)

Haverhill is no exception in following the laws and customs of Essex County. In the early 1650’s, there are divisions of land; settling of millers and sites; hiring a preacher, appointing a herdsman, and setting their salaries; admitting a blacksmith and tailor to the town; and prosecutions for violation of laws we would find peculiar by today's standards. (Chase, p.79)

The development of the social order and authority must make some impression on Jonathan during his formative years. On one hand, there is a dress code that applies only to people worth less than ₤200. The wives of Joseph Swett and John Hutchins wear silk hoods, but only Goodwife Swett will be prosecuted and pay a fine of 10 shillings, according to a 1650 law against "intolerable excess and bravery in dress." (Chase, p.79) This social evolution also leads to a demand for accountability and transparency. The town voted in 1652 that the selectmen – the city council of the day – "give in their account what they have received, and what they have disbursed." (Chase, p.80)

About that time, Lt. Robert Pike, leader of the Salisbury militia and ancestor to militia colonels and the explorer, Zebulon Pike, is "disfranchised" and "heavily fined" by the General Court of the colony for defending the right of Joseph Peasley, of Haverhill, and Thomas Macy, of Salisbury, to speak freely of their religious faith in the "absence of a minister." Pike declares that the General Court "did break their oath to the country, for it is against the liberty of the country, both civil and ecclesiastical." In response to the court’s fine, "a large number of inhabitants of Hampton, Salisbury, Newbury, Haverhill, and Andover" petition the court to have Pike’s sentence revoked. Thirty-seven of the petitioners, including Richard Singletary, are from Haverhill – representing a large majority of that town. The court, in turn, is "highly indignant that 'so many persons should combine together to present such an unjust and unreasonable request'" in response to the court's unjust and unreasonable judgment. (Chase, p.80) These are the times of their lives. In a world with no Internet or television, few books, and the news of the day passes by word of mouth and pamphlets, what lessons does a teenager take from these kind of events?

This type of controversy is not limited to the colonies. In England, homeland to these immigrant ancestors, the Interregnum is a time of much spiritual exploration. Just as a prime motivation for emigration is the religious freedom spoken of by Robert Pike above, the seeds of change sprout into a variety of belief systems or faiths. As the reader browses the next bit of this chapter concerning the various religious beliefs explored during Jonathan’s teenage years, try listening to Manic Street Preachers Radio for a modern expression of this rebelliousness. Crank up the speakers - if you dare. Some of us may relate to this use of sound to express feeling. Others may find a better appreciation of the Puritan reaction to a similar use of sound and music in their day, when simply singing and chanting one's faith is often unwelcome.

In the early 1650's, George Fox, an ex-army officer and religious sectarian, received a series of revelations from which he understood that salvation from sin was open to all people if they would be redeemed by God's "light of truth" within them. Scripture and even knowledge of Jesus were incidental to the power of God made manifest in the human heart. During the early years of the decade Fox traveled throughout the North and West of England, preaching and converting those sympathetic to radical religion.

Fox's adherents frequently met in silence, waiting upon the spontaneous prompting of the spirit within them before speaking. In contrast to their Puritan neighbors, they believed that the introspective inner light could search and burn out all hidden sins. The process of unrelenting introspection could be accompanied by shaking (hence the name Quaker), crying, groaning, collapsing, and other outward signs of the struggle within. Once this agonizing victory of spirit over human nature had been accomplished, Quakers held themselves to be fully redeemed. Fox understood human perfection to be attainable, for he experienced a vision in which "All things were new, and all the creation gave another smell unto me than before, beyond what words can utter. I knew nothing but pureness, and innocency, and righteousness, being renewed up into the image of God by Christ Jesus, so that I say I was come up to the state of Adam which he was in before he fell." (Enright)

I find it useful at this point to refer to Laurence Claxton and his account of his experimentation with various forms of spirituality that began for him in 1630 at the age of fifteen and lasted to at least 1660 with the publication of his account of it, The Lost Sheep Found: or, The prodigal returned to his Fathers house, after many a sad and weary Journey through many Religious Countrys. While it should not be regarded as an objectively valid report of his infamous activities, I think this autobiographical piece is a fair litany of his views. Little else espoused or published by the free thinkers of the day survives since they were, by definition of the authorities, heretical. Perhaps this survived since, in it, he admits unabashedly to his blasphemous speech and debauching ways. Sexuality and power seemed to be the ever pervasive, underlying, intermingling motivations throughout these controversies. As one might expect, sexuality and power are themes intermingled throughout human history.

For thirty years, Claxton immersed himself in several alternative faiths and preached in some. He was raised Episcopalian – the Church of England in that day – and found himself too far removed from a knowledge of God. He then briefly tried being a Presbyterian and found it profoundly oppressive. A move to the Independents seemed reactionary to the previous experience. In seeking the Truth there, he was instead repelled by an exclusivity and disparity of others that was not reflected in his understanding of Christ. He found himself yet no closer to God.

He then found liberty in the informal sharing of faith in private homes until inspired by Paul Hobson's eloquence to find his own voice as an Antinomian preacher. (Learn more about Winthrop’s political rival, Ann Hutchinson, and the colonial New England expression of this philosophy.) In this phase, Claxton also spent some time as a soldier, before devoting himself to itinerant preaching and found an ability to inspire beliefs in other people.

Next, as a Baptist, he "dipped" many people in an available body of water. This activity warranted disrobing and the wearing of a nightshirt to save spoiling one’s clothes in the water and catching a chill. The authorities considered this naked cavorting and for this, and his popularity at so doing, he was called before Parliament for reprimand. It was also at this time he makes note of affection with women, in particular, including the daughters of one with whom he took shelter while in Suffolk. It is one of these daughters whom he would later profess to having married by his own words in ceremony in her father’s house with his blessing. This, too, was not the orthodox tradition of the time or according to the law. Put under house arrest, he continued to preach from his room until he affected his release with a promise to stop preaching Baptism and dipping people.

He leaves his wife in Suffolk and becomes a Seeker of the Truth. Among others of like beliefs in London, he finds companionship and writes a book. He leaves there to continue his travels with the help and kindness of others, preaching to those that would listen, associating with kindred spirits, and lying with women other than his wife. Eventually, he makes the acquaintance of Abiezer Coppe, a Prophet of the Ranters and author of Some Sweet Sips of Some Spiritual Wine and A Fiery Flying Roll. Claxton enters the wilderness of a loose association known of Ranters, known for their hectic, impassioned, experientially-inspired discourse peppered with biblical references as depicted in this 1650 woodcut from the British Library Board. In this phase, Claxton wrote A Single Eye All Light, no Darkness. It is this association for which he was most remembered (Plant) and the basis for the name of an English Indie Rock band, Laurence Claxson and the Ranters. It is for his writings and this association for which he is brought before Parliament.

Having not found God or the Devil in any of these seven faiths, he turned to those that call themselves Friends and their critics call Quakers. However, he finds them vain and oppressive in their belief that they know best of God’s will, particularly the preaching of George Fox. Claxton is then found in 1650 among the Muggletonians as he writes his memoir.

I relate all this because it seemed a useful way to convey a sense of the beliefs with which Jonathan was directly or indirectly familiar throughout his life. Claxton’s exploits relative to the governmental authorities and the social order are enlightening in the context of the colonial quest for freedom of religion and self-governance. Vestiges of this persist today. This seems to me to be a prevailing theme in Jonathan’s own journey. One has to ask what influence these controversies had on him regardless of any familiarity he may have had with Claxton by name or reputation.

Meanwhile, back in 1652 Newbury, Masachusetts, the town voted to build a school and hire a teacher (Dow, p.70) and no longer depend on Ipswich for such services. Lt. Pike was one of the four men selected to oversee the operation. While Haverhill had grown considerably from the 32 land holders and several families that attended church in the past ten years it had not reached the required threshold of fifty according to the 1647 law.

While Salisbury had sufficient population and established a school about that time, Haverhill did not yet have a "Latin" school to teach reading and writing until the 1660’s. Despite the existence of cart path grade highways, it seems doubtful that Jonathan would have either returned some twelve miles and cross the Powow River to Salisbury or cross the Merrimack by ferry and travel the several more miles to Newbury against the threat of wild dogs, wolves, and Indians in order to attend school on any regular basis. He may have attended Salisbury prior to their move to Haverhill, but was more likely, I think, to have been home schooled.

Because of a 1645 law, all youth from ten to sixteen years of age would be "instructed upon ye usual training days (Saturday), in ye exercise of armes, as small guns, halfe pikes, bowes and arrowes, &c." Jonathan, at this time age 12, would be no exception. His father would have also participated in military exercises on the town commons as part of a "train band" or militia that existed there from Haverhill’s beginnings as a defense against Indian attack. (Chase, p.66) Each citizen was required to provide their own weapon, which they would also bring to church on Sabbath - less they succumb to a surprise attack while congregated in worship, as did happen during a court session in Salisbury in 1653. (Merrill, p.49) In fact, a protocol persisted for many years from the practice of having the men seated together near the door to the meeting house so as to be at the ready. They would take turns stand guard by the door and, at the conclusion of services, exit first as a precaution to ensure the safety of the women and children.

Since the house lots were still clustered near the center of town and as this would seem something of a "right of passage" for the boys, I suppose that some of the wives and their children may have come out to the town green for some of these training days to watch as entertainment while sharing the news of the day. This may have been quite an event on more pleasant days of summer.

The sergeant, an elected position, would put them through their practice at loading (termed "charging") and firing their fowling-pieces. These weapons were crude and difficult to use, but lighter in weight than the muskets of that day; capable of being held to the shoulder and aimed without the use of a stand or an assistant. Speed of reloading properly was of the utmost importance during battle.

The leader would likely first rehearse the basics of pouring the precise amount of powder from a pouch or horn carefully down the muzzle – pointed up - so that it would settle fully in the bottom and not stick to the side. This was best done when the muzzle was yet hot from the previous round to prevent sticking to any moisture that might form a humid days. The correct technique would then include a gentle, but firm, tap of the butt to the ground to set all the powder into place. Then, the round lead shot was dropped in. It, of course, needed to be properly formed and stashed in a ready pouch prior to the exercise.

After that a wad of paper, cloth, or moss could be placed in the barrel and pushed down to the load with a tap or two of the ramrod. Too hard of a tap could bruise the powder, diminishing the explosion, or spread the soft lead, causing the pellet to stick and exploding in one’s face when fired. Firing required priming to get powder positioned behind a small hole and touching the hole with a match to ignite the powder. (Magné de Marolles)

A sergeant so inclined with a playful mood might have raised a twitter from the onlookers by admonishing the men to treat the loading firmly but gently "as though handling a woman."

Targets would be established 70 or so yards away that the boys might be induced to maintain between shots. Firing the weapon required priming, to see powder in the pan, and lighting it with a match. The sergeant would then command "ready, aim, fire! Reload, men." This then repeated, perhaps quite methodically, for some time to improve that all-important speed of reloading. It is not recorded who commanded the Haverhill militia until 1665 when Nathaniel Saltonstall was chosen Captain. (Chase, p.108) One has to suspect he served that role during some of the intervening years as he did for many subsequent years.

As Jonathan enjoys his teenage years, his father is settling his family into a life-long residence in Haverhill. In 1653, Richard receives a division of land there. And in 1655, he becomes a proprietor and town officer, termed "selectman". (Barry, p.392; Hoyt; Pope, p.416) Then Benjamin is born April 04, 1656, to Richard and Susannah. (MA-VR)

This is also an active time for commercial development as one of the first of many mills is approved and built.(Mirick, p.34 ) It would seem the opportune time for Jonathan to learn about their construction and operation.

Religion, social governance, and the courts continue to be intertwined in this society as Mrs. Holgrave, of Salem, is presented to a jury for reproachful and unbecoming speeches against Mr. William Perkins, officer of the church. Her crime is to opine that "the teacher was soe dead" and "the teacher was fitter to be a ladyes chamberman, then to be in the pulpitt." (Essex Court Records, v.I, p.275)

In October, 1657, a law is declared that "the penalty for entertaining quakers should be forty shillings." (Coffin & Bartlett, p.61) The next year more laws are enacted preventing Quakers or their sympathizers from becoming freemen or exercising voting privileges. There were several instances involving numerous men and women prosecuted and imprisoned for being Quakers and, therefore, suspected of witchcraft, as well. On June 3, Quaker Humphrey Norton confronts Governor Thomas Prence during his court appearance for entering the colony contrary to law. December 3, the Plymouth Court attempts to prevent Quakers from coming to Sandwich by sea by seizing any boats carrying them. (Plimouth Plantation; McInnes)

In 1659, several persons were prosecuted and fined for violating the law of 1657 prohibiting the entertaining of Quakers. Among them was Thomas Macy, who explained in letter to the court that he meant no offense. That Edward Wharton and three others came to his house on a hard raining morning and asked directions to Hampton and the distance to Casco Bay. He recognized Wharton and did not ask the other's names yet observed the appeared to be Quakers. They stayed but ¾ hour and spoke with them very little as he was wet from having just been outside and his wife was sick in bed. They went on their way and he never saw them again. Macy was fined 30 shillings and immediately thereafter took his wife and children in an open boat to settle on Nantucket, never to return to Puritan territory. Two of the men, William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephensen were then hung in Boston on December 27th. (Coffin & Bartlett, pp.62-63)

Notoriously, witchcraft and other acts of the devil became a common way to explain the unexplainable. "In 1658, a singular case of this kind occurred in Essex County. The following papers relating to it illustrate the sentiments and forms of thought prevalent at that time, and give an insight of the state of society in some particulars:--"

To the Honored Court to be holden at Ipswich, this twelfth month, '58 or '59.

HONORED GENTLEMEN,--Whereas divers of esteem with us, and as we hear in other places also, have for some time suffered losses in their estates, and some affliction in their bodies also,--which, as they suppose, doth not arise from any natural cause, or any neglect in themselves, but rather from some ill-disposed person,--that, upon differences had betwixt themselves and one John Godfrey [b. 1620; EQC 2:250], resident at Andover or elsewhere at his pleasure, we whose names are underwritten do make bold to sue by way of request to this honored court, that you, in your wisdom, will be pleased, if you see cause for it, to call him in question, and to hear, at present or at some after sessions, what may be said in this respect.

JAMES DAVIS, Sr., in the behalf of his son EPHRAIM DAVIS.

JOHN HASELDIN, and JANE his wife.

ABRAHAM WHITAKER, for his ox and other things.

EPHRAIM DAVIS, in the behalf of himself.

"The petitioners mention in brief some instances in confirmation of their complaint. There are several depositions. That of Charles Browne and wife says: --"

About six or seven years since, in the meeting-house of Rowley, being in the gallery in the first seat, there was one in the second seat which he doth, to his best remembrance, think and believe it was John Godfrey. This deponent did see him, yawning, open his mouth; and, while he so yawned, this deponent did see a small teat under his tongue. And, further, this deponent saith that John Godfrey was in this deponent's house about three years since.

Speaking about the power of witches, he the said Godfrey spoke, that, if witches were not kindly entertained, the Devil will appear unto them, and ask them if they were grieved or vexed with anybody, and ask them what he should do for them; and, if they would not give them beer or victuals, they might let all the beer run out of the cellar; and, if they looked steadfastly upon any creature, it would die; and, if it were hard to some witches to take away life, either of man or beast, yet, when they once begin it, then it is easy to them.

"The depositions in this case are presented as they are in the originals on file, leaving in blank such words or parts of words as have been worn off. They are given in full."

"THE DEPOSITION OF ISABEL HOLDRED, who testifieth that John Godfree came to the house of Henry Blazdall, where her husband and herself were, and demanded a debt of her husband, and said a warrant was out, and Goodman Lord was suddenly to come. John Godfree asked if we would not pay him. The deponent answered, 'Yes, to-night or to-morrow, if we had it; for I believe we shall not ... we are in thy debt.'

John Godfree answered, 'That is a bitter word;' ... said, 'I must begin, and must send Goodman Lord.'

The deponent answered, '... when thou wilt. I fear thee not, nor all the devils in hell!' And, further, this deponent testifieth, that, two days after this, she was taken with those strange fits, with which she was tormented a fortnight together, night and day. And several apparitions appeared to the deponent in the night. The first night, a humble-bee, the next night a bear, appeared, which grinned the teeth and shook the claw: 'Thou sayest thou art not afraid. Thou thinkest Harry Blazdall's house will save thee.'

The deponent answered, 'I hope the Lord Jesus Christ will save me.'

The apparition then spake: 'Thou sayst thou art not afraid of all the devils in hell; but I will have thy heart's blood within a few hours!'

The next was the apparition of a great snake, at which the deponent was exceedingly affrighted, and skipt to Nathan Gold, who was in the opposite chimney-corner, and caught hold of the hair of his head; and her speech was taken away for the space of half an hour. The next night appeared a great horse; and, Thomas Hayne being there, the deponent told him of it, and showed him where. The said Tho. Hayne took a stick, and struck at the place where the apparition was; and his stroke glanced by the side of it, and it went under the table. And he went to strike again; then the apparition fled to the ... and made it shake, and went away. And, about a week after, the deponent ... son were at the door of Nathan Gold, and heard a rushing on the ...

The deponent said to her son, 'Yonder is a beast.'

He answered, ''Tis one of Goodman Cobbye's black oxen;' and it came toward them, and came within ... yards of them. The deponent her heart began to ache, for it seemed to have great eyes; and spoke to the boy, 'Let's go in.'

But suddenly the ox beat her up against the wall, and struck her down; and she was much hurt by it, not being able to rise up. But some others carried me into the house, all my face being bloody, being much bruised. The boy was much affrighted a long time after; and, for the space of two hours, he was in a sweat that one might have washed hands on his hair. Further this deponent affirmeth, that she hath been often troubled with ... black cat sometimes appearing in the house, and sometimes in the night ... bed, and lay on her, and sometimes stroking her face. The cat seemed ... thrice as big as an ordinary cat.""THOMAS HAYNE testifieth, that, being with Goodwife Holdridge, she told me that she saw a great horse, and showed me where it stood. I then took a stick, and struck on the place, but felt nothing; and I heard the door shake, and Good. H. said it was gone out at the door. Immediately after, she was taken with extremity of fear and pain, so that she presently fell into a sweat, and I thought she would swoon. She trembled and shook like a leaf.

THOMAS HAYNE"NATHAN GOULD being with Goodwife Holgreg one night, there appeared a great snake, as she said, with open mouth; and she, being weak,--hardly able to go alone,--yet then ran and laid hold of Nathan Gould by the head, and could not speak for the space of half an hour."

NATHAN GOULD"WILLIAM OSGOOD testifieth, that, in the yeare '40, in the month of August,--he being then building a barn for Mr. Spencer,--John Godfree being then Mr. Spencer's herdsman, he on an evening came to the frame, where divers men were at work, and said that he had gotten a new master against the time he had done keeping cows. The said William Osgood asked him who it was. He answered, he knew not. He again asked him where he dwelt. He answered, he knew not. He asked him what his name was. He answered, he knew not.

He then said to him, 'How, then, wilt thou go to him when thy time is out?'

He said, 'The man will come and fetch me then.'

I asked him, 'Hast thou made an absolute bargain?'

He answered that a covenant was made, and he had set his hand to it. He then asked of him whether he had not a counter covenant.

Godfree answered, 'No.'

W.O. said, 'What a mad fellow art thou to make a covenant in this manner!'

He said, 'He's an honest man.' --

'How knowest thou?' said W.O.

J. Godfree answered. 'He looks like one.'

W.O. then answered, 'I am persuaded thou hast made a covenant with the Devil.'

He then skipped about, and said, 'I profess, I profess!'"

WILLIAM OSGOOD

As this decade draws to a close,

the proceedings against Godfrey were carried up to other tribunals, as appears by a record of the County Court at Salem, 28th of June, 1659:--

"John Godfrey stands bound in one hundred pound bond to the treasurer of this county for his appearance at a General Court, or Court of Assistants, when he shall be legally summonsed thereunto."

What action, if any, was had by either of these high courts, I have found no information. But he must have come off unscathed; for, soon after, he commenced actions in the County Court for defamation against his accusers; with the following results:

"John Godfery plt. agst. Will. Simonds & Sam.ll his son dfts. in an action of slander that the said Sam.ll son to Will. Simons, hath don him in his name, Charging him to be a witch, the jury find for the plt. 2d damage & cost of Court 29sh., yet notwithstanding doe conceiue, that by the testmonyes he is rendred suspicious."

"John Godfery plt. agst. Jonathan Singletary defendt. in an action of Slander & Defamation for calling him witch & said is this witch on this side Boston Gallows yet, the attachm.t & other evidences were read, committed to the Jury & are on file. The Jury found for the plt. a publique acknowledgmt, at Haverhill within a month that he hath done the plt. wrong in his words or 10sh damage & costs of Court £2-16-0."

Godfrey was a most eccentric character. He courted and challenged the imputation of witchcraft, and took delight in playing upon the credulity of his neighbors, enjoying the exhibition of their amazement, horror, and consternation. He was a person of much notoriety, had more lawsuits, it is probable, than any other man in the colony..."

The preceding documents some of the social hysteria regarding witchcraft prevalent among the Essex County colonists, yet 30 years before the infamous witchcraft trials of Salem. (Upham, pp.429-433; Ray v.II, pp.157-161) It also serves to highlight just some of the numerous incidents in which John Godfrey, quite apart from any other in the colony, seems to use the superstitious nature of the common religious beliefs of the time to take advantage, to extract some payment, or for entertainment. And he usually escapes punishment. He may even have established a reputation for manipulating the courts as the herdsman sometimes acts as attorney for others in pressing charges against his neighbors.

Superstition, litigation, prejudice, persecution of Quakers and others that would question authority - it is in this environment in 1659 that Jonathan and Mary probably marry and have their first child, Esther, at Haverhill or Newbury. How their romance began is unrecorded. The Singletary's lived on one side of the Merrimac and the Bloomfields on the other. So contact was not likely daily. We have seen that Richard was settled in Haverhill for a few years. And, according to the 1698 will of William Dole, the Bloomfield family lived adjacent to the Dole and Spencer farms near the Lower Green in Newbury. (Currier, p.18) Perhaps their romance was kindled early in the year at the wedding of Jonathan's 16 year old sister, Eunice, who is said to marry 31 year old Thomas Eaton on January 6, a day before her 17th birthday and just a couple weeks before Jonathan's 19th birthday. The vital records are unclear on this wedding date as the VR of Andover reads "January 6, 1658" (MVRP) and Haverhill records read "Dec. ––, 1678 [1658?.]" (MVRP) Noting that this is also an awkward date reference to translate from the double-dating system of that time, the true date is either the 10th month [December] 1658/59 or the 6th day of the 11th month [January] 1658/59, I am accepting here January 6, 1659, give or take a couple weeks.

A Sketch of the History of Newbury, Newburyport, and West Newbury, Joshua Coffin and Joseph Bartlett, 1845.

An Essay on Shooting, Gervais François Magné de Marolles, 1789.

British Civil Wars, Commonwealth and Protectorate, 1638-60, David Plant, 2010.

Early Vital Records of Massachusetts, 1600-1850, Massachusetts Vital Records Project, 2005-2010.

History of Amesbury, Joseph Merrill, 1880.

History of Framingham, William Barry, 1847.

The Oppression of Prophecy: Quaker Women in Late Seventeenth Century Yorkshire: Writings by Judith Boulbie and Mary Waite, an electronic edition., Amy Enright, 2005.

Old Families of Salisbury and Amesbury, David W. Hoyt, 1889

"Ould Newbury": Historical and Biographical Sketches, John J. Currier, 1896.

Pioneers of Massachusetts, Charles Henry Pope, Heritage Books, 1900.

Timeline of Plimouth Colony 1620-1692, Plimouth Plantation, 2008.

Records and Files of the Quarterly Court of Essex County, Massachusetts, Volumes 1-4, Massachusetts County Court (Essex County), George Francis Dow, Massachusetts. Inferior Court (Essex County), Essex Institute, 1921.

Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Benjamin Ray, The Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia, 2002.

Salem Witchcraft, Volumes I and II, Charles Upham, 1969.

The Colonial History of Hartford, William DeLoss Love, 1914.

The History of Haverhill, Massachusetts, Benjamin L. Mirick and John Greenleaf Whittier, 1832.

The History of Haverhill, Massachusetts, George Wingate Chase, 1861.

The Quaker "Invasion" and Religious Violence in Massachusetts, Andrew McInnes, 2007.

This decade follows the apparent acquittal of John Godfrey on witchcraft charges and years of strange encounters, cursing speeches, drunkenness, stealing, and problematic business deals between Godfrey and his neighbors throughout the county. (Upham, p.429; Hall, p.114; Demos, p.36-50)

The first half of this decade Jonathan and Mary begin raising their young family together in Haverhill. They are likely living with his parents as court records dated October 8, 1662, state "The warrant was left at Jonathan Singlltary's father's house, where Jonathan resided." (Ray, v.3 p.6)

In March 1661, John Godfrey successfully sues Edward Clarke over a half paid debt of corn and wheat that he wanted put in a tub at Goodman Singletree's. This is likely Jonathan Singletary as court records over the next two years seem to associate Jonathan with this band of corn. John Griffin and Job Tiler testify to witnessing partial payment at Clarke's house. It seems a typical example of how Godfrey involves multiple people and seems reluctant to settle the deal without going to court. (Ray, v.2 p.274)

On May 5, Jonathan's cousin, Philip Cooke, is baptized by Jonathan "Matchless" Mitchell at First Church of Cambridge. He is the second of that name to have been born into that family group. Sadly, the baptism is just one week before the death of Susanna's young niece, Sarah Cooke. (Savage, p.449) Jonathan will later recall a sermon by Mitchell that provides him some comfort while in the Ipswich jail. Perhaps the baptism of his cousin is the very occasion of the reassuring sermon and/or if they were yet there for a service for Sarah. This also provides us more evidence of Susanna's connection with the elder Phillip of that town and that Jonathan may have travelled to Cambridge with his mother for the baptism of her nephew.

June 5, Charles II is restored to the throne. Upon receiving word, the inhabitants of New Plymouth declare themselves loyal subjects. Just three days later laws against Quakers are repealed as Charles expresses his displeasure regarding such an expression of religious prejudice in the governance of the colonies. (Plimouth Plantation)

On December 29, a second daughter, Mary, is born to Jonathan and Mary. She will die within two years, perhaps in birth or shortly thereafter as there is no record of her death. Certainly she passed sometime during the extended controversy with Godfrey already unfolding since another by that name is born in early 1664. (MVRP) What effect these troubles had upon her death or her death upon Jonathan's actions one can only wonder. We do know that Jonathan and Mary's next child will not be born in Massachusetts.

Just two and a half months later, Jonathan, his father, and father-in-law have some difficult dealings with Godfrey in order to settle a dispute over a band of corn in a barter between Godfrey and Clarke. Upon Feb. 18, 1662, Richard Singletary and Thomas Bloomfield are in Ipswich as agents for Jonathan Singletary, who is then in that town's jail upon several executions of John Godfrey. They tender said Godfrey a parcel of land in satisfaction of these executions. Richard recalls in later testimony their discussion as follows. (Ray, v3 p.27)

John Godfrey said, "Ye land I will never meddle wth except ye Law constraineth me to take it." And so turned his back.

"Nay stay, John," said one of us "and let us have a few words with you. Our coming is to make a full and final end between Jonathan and you if we can without any more law."

"Well," said Godfrey, "as for ye land I will not meddle with but if you will fetch me or pay me in goods for these executions which he is now in prison upon, I will give him a full and general acquittance of all debts and dues and all things, etc."

Godfrey said he would take the goods whenever they were brought to him.

While Jonathan is in Ipswich jail, Richard Singletary and Thomas Bloomfield come to John Todd’s house for some goods to redeem their son out of prison. Todd delivers to Thomas Bloomfield a hundred odd yards of canvas, which the latter took away, both promising to pay Todd for it. At Todd's house, Anthony Austin asks Thomas Bloomfield to whose account the canvas is to be charged. Bloomfield replies that it did not matter. Austin, having Singletary’s account ready at hand, charged it to him. According to court records, Anthony Austin makes a deposition to this effect and a copy is made, Feb. 2, 1663, by Robert Lord, cleric. Austin will swear to it in Ipswich court, Sept. 29, 1663, before Robert Lord, cleric. Lord later deposes that he was at Mr. Wilson’s when Richard Singletary and Thomas Bloomfield were there to see after redeeming Jonathan out of prison. Lord had part of the goods for fees and the rest was delivered to John Godfrey and the keeper of the prison. (Ray, v.3, p.214)

And Jonathan will later recall this curious incident with Godfrey while he sits in the Ipswich jail. (Upham, v.1 p.434)

Date the fourteenth the twelfth month, '62. -- The Deposition of Jonathan Singletary, aged about 23, who testifieth that, I being in the prison at Ipswich this night last past between nine and ten of the clock at night, after the bell had rung, I being set in a corner of the prison, upon a sudden I heard a great noise as if many cats had been climbing up the prison walls, and skipping into the house at the windows, and jumping about the chamber; and a noise as if boards' ends or stools had been thrown about, and men walking in the chambers, and a crackling and shaking as if the house would have fallen upon me.

I seeing this, and considering what I knew by a young man that kept at my house last Indian Harvest, and, upon some difference with John Godfre, he was presently several nights in a strange manner troubled, and complaining as he did, and upon consideration of this and other things that I knew by him, I was at present something affrighted; yet considering what I had lately heard made out by Mr. Mitchel at Cambridge, that there is more good in God than there is evil in sin, and that although God is the greatest good, and sin the greatest evil, yet the first Being of evil cannot weane the scales or overpower the first Being of good: so considering that the author of good was of greater power than the author of evil, God was pleased of his goodness to keep me from being out of measure frighted. So this noise abovesaid held as I suppose about a quarter of an hour, and then ceased: and presently I heard the bolt of the door shoot or go back as perfectly, to my thinking, as I did the next morning when the keeper came to unlock it; and I could not see the door open, but I saw John Godfre stand within the door and said, 'Jonathan, Jonathan.'

So I, looking on him, said, 'What have you to do with me?'

He said, 'I come to see you: are you weary of your place yet?'

I answered, 'I take no delight in being here, but I will be out as soon as I can.'

He said, 'If you will pay me in corn, you shall come out.'

I answered, 'No: if that had been my intent, I would have paid the marshal, and never have come hither.'

He, knocking of his fist at me in a kind of a threatening way, said he would make me weary of my part, and so went away, I knew not how nor which way; and, as I was walking about in the prison, I tripped upon a stone with my heel, and took it up in my hand, thinking that if he came again I would strike at him.

So, as I was walking about, he called at the window, 'Jonathan,' said he, 'if you will pay me corn, I will give you two years day, and we will come to an agreement.’

I answered him saying, 'Why do you come dissembling and playing the Devil's part here? Your nature is nothing but envy and malice, which you will vent, though to your own loss; and you seek peace with no man.'

'I do not dissemble,' said he: 'I will give you my hand upon it, I am in earnest.'

So he put his hand in at the window, and I took hold of it with my left hand, and pulled him to me; and with the stone in my right hand I thought I struck him, and went to recover my hand to strike again, and his hand was gone, and I would have struck, but there was nothing to strike: and how he went away I know not; for I could neither feel when his hand went out of mine, nor see which way he went."

As Upham describes it in a discussion of the witchcraft hysteria of the time, "there is one particularly interesting item in Singletary's deposition. It illustrates the value of good preaching. This young man, in his gloomy prison, and overwhelmed with the terrors of superstition, found consolation, courage, and strength in what he remembered of a sermon, to which he had happened to listen, from Matchless Mitchel.' It was indeed good doctrine; and it is to be lamented that it was not carried out to its logical conclusions, and constantly enforced by the divines of that and subsequent times." (Upham, v.1 pp.434-437) In the context of John Godfrey's odd behaviors and taunting ways, one might otherwise see how faith can make room for reason to confront an antagonist rather than be overwhelmed by superstition or attempts to terrorize. Why do so many "divines" today rely so little on this Christian faith? One wonders what faith it is upon which these "divines" do rely for all this time?

The Ipswich jail is just the second in the county, built ten years earlier in 1652-3. The structure is round and of three stories, with height and windows similar in design to the watch-house nearby. From the description above, it would seem there is a cell on the first floor and Jonathan is the only prisoner kept there that night with no keeper in attendance. This jail becomes so infamous for a holding cell for witches awaiting trial and execution that some say the very ground upon which it stands is yet haunted today. (Bennett; Arrington, v.1 p.48)

On March 20, Richard Singletary and Susanna, his wife, depose that "John Godfrey being occasionally at their house said, concerning the corn in controversy, that he thought he should never get it of Goodman Clarke for he would pay him in papers as he did the last year. Godfrey said several times, 'I would rather it were in a heap in ye street and all ye town hogs should eat it than he should keep it in his hands.'" (Ray, v.3 p.40) Eleven days later the court in Ipswich heard the case of John Godfrey v. Jonathan Singletary for a debt of £8 in wheat and Indian corn. The verdict is for Singletary. (Ray, v.3 p.39)

April 8, Richard and Susanna convey to Jonathan's wife, Mary, 150 acres of upland and meadowland in Haverhill "up ye river to the west end of town in ye 3d division." Eighty acres of this land was bounded by the lots of Theophilus Satchwell and Thomas Lilford, 70 acres on the south side of Spicket River, and nearly seven acres of "accomodations" belonging to it. [probably a village houselot and access to common grounds] (Perley, v.3 p.1087) It is difficult to know if this first parcel of land is the same land Jonathan's father offered to John Godfrey to settle their differences two months earlier. Perhaps it is just coincidence that later the same month Richard describes that offer in testimony in the case.

At about this time yet seemingly of a separate matter, Edward Youmans encounters John Godfrey with Jonathan Singletary coming out of Rowley, and deponent asks if said Godfrey might lend him five shillings and he says "he could not for he had lent Jonathan Singletary all the money he had." (Ray, v.3 p.6-7) Most curious here is that Godfrey would lend any money to Jonathan when he considered Jonathan already in debt to him or that Jonathan would borrow from Godfrey while their last deal remains unresolved.

In May, John Godfrey says to Abraham Whitaker that he gave Jonathan Singletary the £8 that Edward Clark owed him, but then says that if he had it in his hands again, Singletary should never have it.

June 10 the commissioners of Haverhill find for John Godfrey when Edward Clark sues him "for not coming to receive a parcel of wheat and Indian corn due upon bond" from "March 1, last." Godfrey delays the proceeding to see that Jonathan Singletary was in attendance. (Ray, v.3 pp.39-40)

Come October 8, John Godfrey sues Jonathan over a bond that Godfrey assigned to Jonathan and was due from Edward Clark to Godfrey (the band of corn?) and for refusing to give him security. As a result, the court orders an attachment of Jonathan’s land lying about a mile beyond the river called Hook’s meadow river, and abutting the river Merrimac on one end and joining next to Goodman "Souhell" (Henry Sewall or Theophilus Sacthwell misspelled?) on one side. The warrant for the attachment is left at Jonathan Singeltary's father's house, where Jonathan resides. (Ray, v.3 p.6) If this refers to Satchwell and not Sewall with property along the Merrimac River town at that time, it may well be that this is some of the same property recently conveyed to Mary yet still vulnerable to attachment by Godfrey's legal actions.

Throughout the period of 1658-1663, John Godfrey is also embroiled in a deal with Daniel Clark, Francies Urselton, Anthony Carroll, William Pritchett, and Phillip Fowler over possession of a house and 26 acres land in Topsfield, involving a payment of £50 from Urleston to Godfrey in 1659 extended to March 1661, a 1660 payment from Godfrey to Pritchett of £59 9s. 8d., and a 1658 debt due in 1662 by Godfrey in wheat and corn. (Ray, v.3 p.23) It would seem that Godfrey engages in a lot of the proverbial "borrowing from the Peter to pay Paul" in his business dealings. John Godfrey is cited again in June 1662 when he gets a judgment in Salem court against Richard Ormsby and is granted an attachment that August of 102 acres of Ormsby land valued at £56. (Ray, v.3 p.21)

At a session of the court in Salem on November 22, Susanna and Richard Singletary provide three statements regarding the dispute between Jonathan and Godfrey, as follows. (Ray, v.3 pp.6-7)

As I had occasion to come by Thomas Lilford where he was at work he said unto me "What will your son, Jonathan, do with Godfrey? He is resolved to have him to court about the band of corn yet he had him of Clark."

And he saith "he will have me for a witnes about it."

"Nay," said I. "It doth not much trouble me for he has given him ye corn if he can get it of Clark. Can you witness yet he promised to give Godfrey security for ye band of corn?"

Thomas Lilford said, "Nay. I heard him speak of security, but I do not know for what it was."

Susana Singletary, aged about forty-six years, also testified that in her own house John Godfrey assigned the band of corn. Richard Singletary, aged about sixty-three, testified, that

as I was going to Salisbury this last Monday past along with John Godfrey, he was in a great passion against Jonathan Singletary at his house a while ago. And I had forty or fifty shillings in money about me and Jonathan would have it, but I considered yet I had often use for money at law and so I did not let him have any.

Judgment is granted John Godfery at Salem Court, November 27. A few days later, John Johnson, Constable of Haverhill, Deputy of Samuel Archard, Marshal of Salem, serves the warrant against Jonathan Singletary.

The year 1663 turns more favorably for Jonathan. On January 12, Jonathan receives land in the third division of Salisbury, Massachusetts. (Myers, p.530)

On March 20, Richard and Susanna Singletary depose that "they asked Thomas Davis about the evidence that he had given at the last Salem court [November 25, 1662], and if he could testify that Jonathan was to give Godfrey security for that corn. Davis said that he could not testify that he gave security for the corn, etc." They then swear to their deposition on the 27th before Simon Bradstreet. However, I find no testimony by Davis that November and wonder to whom they refer with the pronoun "he." On this occassion, they also deposed a repeat of their testimony from November 22 regarding Godfrey's statements at their house.

The last day of March the issue with John Godfrey and Jonathan's liability in Edward Clark's debt of corn to Godfrey is almost fully settled in Ipswich. This is the same town where Jonathan spent the night in jail more than a year earlier. The judges are Mr. Bradstreet, Mr. Symonds, Major General Denison, Major Hathorne and Mr. Woodman. The jurists are Lt. Appleton, Joseph Mettcalfe, Thomas Bishop, Mr. Rogers, Thomas Low, Robert Day, Hercules Woodman, Robert Addams, William Cottle, James Barker, Ezekiell Northend and William Nicolls. Entered into evidence are the:

The court hears Jonathan's suit against Godfrey "for not giving [Jonathan] a general acquittance." John Woodum, Theophilus Wilson and Robert Lord, Marshal, testify that

when Jonathan Singletary and John Godfrey were in said Wilson's house, Singletary was answering the said Godfrey for the executions for which he was put into prison and agreed to end all, but Jonathan said, "If I answer for all it may be when I come to Haverill. The constable will serve them." Godfrey said he would give him an acquittance for them, so when the goods were delivered to John Godfrey, Singletary put an attachment upon them in an action of review.

In addition to the testimony of Jonathan's father and father-in-law about their offer to settle the dispute, Theophilus Wilson certifies that Godfrey received the goods. The court grants Jonathan "an acquittance from the beginning of the world to Feb. 18, last." (Ray, v.3 p.27-28) That would be the time when the 23 year old Jonathan is jailed for slandering Godfrey in a youthful outburst, i.e., calling him a witch, and would seem to absolve him of that offense as well as resolve the underlying issue of debt.

Later in that session, the court hears Godfreys suit against Jonathan for £8 in wheat and corn. The jury decides for Singletary and the court accepts the verdict "provided [Singletary] except in his general acquittance to save said Godfrey harmless from Edward Clarke about his bond of £8." (Ray, v.3, pp.39-40)

June 20, 1663, Theophylus Satchwell dictates his last will and testament to Jonathan Singletary. He and Edward Clarke witness the will, which is proved in October 1663. Perhaps to help settle a dispute among Satchwell's heirs, Jonathan swears an oath to that effect in 1680. (Dow, v.1 p.425)

Come June 28, Godfrey wins a suit against George Hadley of Rowley for a debt of "thirty-three bushels of wheat which said Hadley had taken up of Robert Clements upon John Godfrey's account." Godfrey attaches 6 [or 36] acres of Hadley's land; most of which is planted with corn. While Hadley acknowledges receipt of the wheat in 1657, Richard and Mary Littlehale testify that

when John Godfrey renewed his bond on March 25, 1661, with George Hadley, they heard said Godfry demand nothing of Hadley save five shillings, which the latter agreed to pay to Bartholomew Heath upon Godfrey's account. Since which at the last Salem court John Godfrey would have sued George Hadley about a receipt of twenty bushels of wheat Hadley had of Singletary upon Godfrey's account, but being put in mind by deponents, that the twenty bushels were contained in the bond, he desisted, but for the thirty-seven bushels of wheat which Godfrey now sued for, they knew not whether it were included in the thirty bushels or not. (Ray, v.3, pp.166-167)

By fall, all is not yet settled for the suits over the bond of corn and wheat that had Jonathan in the Ipswich jail a year and seven months earlier. On September 22, 1663, the court hears the suit of John Todd v. Thomas Bloomfield regarding a debt for a "parcel of canvas" used to bail Jonathan out of jail. The verdict is for John Todd. His bill of cost to the court is £1 1s. 4d. Robert Lord, Marshal of Ipswich, serves the action against Bloomfield by taking two of Bloomfield's heifers valued at £7 10s. and delivers them to John Todd on account of the canvas.

A year later at Salem, the court hears Thomas Bloomfield v. John Todd in a review of an action of £6 tried November 29, 1663, at Ipswich court.

Thomas Blomfield’s plea:

- First, that he was arrested for a debt to John Tod, but nothing appeared on the latter’s books.

- Second, that according to the books, the debt was charged to Richard Singletary, who should be sued for the amount instead of himself.

- Third, that even if Anthony Austin said he he was engaged to pay it, the evidence of one man ought not to be sufficient to take away a man’s estate, which would be contrary to law on the first page.

- Fourth, that Austin’s evidence that the cloth was delivered to him was a mistake, for John Tod laid it upon his horse and he was forced to carry it to Ipswich because Richard Singletary was sick, and disposed of it according to Singletary’s appointment.

- Fifth, that Mr. Tod had two young heifers, which were both with calfe, etc.

Answer:

- First, that he was arrested for what was engaged as per testimony of Anthony Austin and Richard Singletary.

- Second, that the book showed canvas delivered, etc.

- Third, one evidence is sufficient.

- Fourth, the cloth was delivered to Bloomfield, who brought it to Ipswich and with it redeemed his son out of prison, and Richard Singletary did not return to Ipswich but went away home.

- Fifth, both were engaged to pay, and John Tod was suing him for only one-half, Singletary having satisfied for his part. "It is too much Ingratitude for Tho. Bloomfield soe ill to requite the sayd Tod for his lose."

William Chandler, aged forty-eight years, deposes that a year earlier, in September 1663, Thomas Bloomfield owned for the debt to John Todd and said it should be paid and if the latter would not enter his action, Bloomfield would pay him in the spring. Robert Lord, Marshal, deposes that he served Bloomfield at that time and submits a copy of the action from 1663.

John Severance is deposed, but I see no record of his statement. Richard Singletary deposes that they took £12 worth of canvas and both engaged to pay John Todd. And John Godfrey and Jonathan Singletary depose that John Todd told them that Richard Singletary and Goodman Blomfield were "able men both & I look only to Goodman Singletary, etc." Anthony Austin, swears to his February 1663 deposition before Robert Lord regarding the record of the transaction at Todd's house in Ipswich court on Nov. 29, 1664, before Daniel Dennison. Robert Lord also swears in court this day to his deposition regarding the transaction. The verdict is for Thomas Bloomfield and his bill of cost is £3 9s. 6d. (Ray, v.3, p.213-214)

Also at court in Salem November 29 we find the herdsman, John Godfrey, acting as attorney to John Todd in an action against William Nicholls over some debt for diverse years. Curiously, Godfrey just testified to Todd's regard for Bloomfield as Bloomfield wins his suit against Todd. William Nicholls was also on the jury the previous spring when Singletary won his case against Godfrey. Godfrey loses this case, as well. (Ray, v.3, p.213-214)

In October 1663, a committee chosen by the General Assembly of the Connecticut Colony sets forth several requirements for the settling of the new plantation in a bay fed by two rivers that provides safe harbor, seafood and fowl, planting land, and sources for water-powered mills. George Fenwick is instrumental in the purchase of the land from the local tribe's sachem, or chief. One of the requirements is that there be 30 families to establish an economically and politically viable community. So another requirement is that any planter who fails to settle there with their family in the first two years would forfeit their land grant which is selected by lot.

The Killingworth community is started with about twenty-two families in the first drawing of lots situated along what is now Main Street set back comfortably from the low-lying harbor area and is a segment of the shoreline path between Guilford and New Haven. Unfortunately, about half of the original families do not satisfy the resettlement requirement. The community is not fully populated until December 1665 with the addition of the following families listed below.

Thomas SMITH, William BARBER, John MEGGS, William KELCEY, Mr. John WOODBRIDGE, Josias ROSITER, Henry FARNAM, William WELLMAN, George CHATFIELD, Thomas STEVENS, Edward GRISWOLD, William HUYTON, Samuel BUELL, John KELCEY, Robert WILLIAMS, granted, John NETTLETON, granted, Annanias TURNERY, purchase, John ROSSITER, by agreement, John MEGGS, granted, John SHETHER, purchase of Jonathan DUNNING, George SANDERS, granted, William STEVENS, Josiah HULL senr., Eliezer ISBEL, granted, Isaac GRISWOLD, purchase, Jonathan DUNIN.

The last of whom listed is Jonathan Dunin. (Buell, 1884; Killingworth Historical Society) Also note there is a Jonathan Dunning listed a few names above Dunin. I believe this indicates Dunning sold his share and never moved to the new settlement. He could easily be confused with Jonathan Dunin. Savage has three Dunning families in New England - George of New Haven, Hicks of Hingham, and Jonathan that served in the Connecticut militia. He also notes that Hicks married Sarah Joy, had Edmund, and that Sarah's father refers to that family in his will as Dunham or Denham. (Savage, p.82)

It would seem that by 1665 Jonathan moved his young family to a settlement along the Connecticut shoreline known at that time as Hammonasset (a part of Killingworth) that is now known as Clinton. It is at this time that he appears to have changed his name as he is there recorded as Dunen, or Dunnin, alias Singletary. (Savage, p.80)

Connecticut was not the only colony encouraging the settlement of new towns at this time. On February 10, 1664, the Proprietors of New Jersey, Lord Berkeley and Sir George Carteret signed a constitution which they distributed to the settlements of New England to encourage settlement in their new land west of Manhatten Island. This document is entitled "The Concessions and agreement of the Lords Proprietors of New Jersey, to and with all and every of the adventurers, and all such as shall settle and plant there." This document was among the first to express principles of self-government and no taxation without representation by conveying to the settlers all the rights granted to the proprietors by the Crown. (Whitehead, v.1, p.37-39)

To encourage planters, every freeman who should embark with the first governor, or meet him on his arrival, provided with a "good musket, bore twelve bullets to the pound, with bandeliers and match convenient, and with six months' provisions for himself," was promised one hundred and fifty acres of land, and the like number for every man-servant or slave, brought with him, provided with the same necessaries. To females over the age of fourteen, seventy-five acres were promised, and a similar number to every Christian servant, at the expiration of his or her term of service. Those going before the first of January, 1665-6, were to receive one hundred and twenty acres, if master, mistress, or able man-servant or slave; and weaker servants, male or female, sixty acres. Those going during the third year, three-fourths, and during the fourth year, one-half of these quantities. On a failure to people their respective tracts within three years, the proprietors reserve the right of conferring them on others.

On the same day the Concessions are signed, Captain Philip Carteret is comminsioned as the Governor of New Jersey. By April of 1665, preparations are complete so he and 30 people, including some servants and Hugenauts that took refuge on his Isle of Jersey, set sail for the New World. They arrive first in Virginia in May, make their way to New York by the end of July, and arrive in the soon-to-be-named Elizabethtown in August.