|

| Family Trees -> Barth Dunham Fitz Randolph Freeman Giles Ilsley Jackson Luthin Venable Waldershelf Wilson |

|

| Family Trees -> Barth Dunham Fitz Randolph Freeman Giles Ilsley Jackson Luthin Venable Waldershelf Wilson |

Havana harbor was a hotbed of activity as the 1750 Spanish treasure fleet readied itself for the long and perilous voyage to Spain. It was August and the hurricane season was already upon them. ... the vessels assembling beneath the mighty guns of Morro Castle numbered just seven. They had been placed under the overall command of Captain-General Don Juan Manuel de Bonilla, a brave and courageous man but one occasionally prone to indecision.

The most important ship was the Admirante, or "admiral" of the fleet, Bonilla's five-hundred-ton, four-year-old, Dutch-built Nuestra Señora de Guadeloupe, alias Nympha. She was owned by Don Jose de Renturo de Respaldizar, commanded by Don Manuel Molviedo, and piloted by Don Felipe Garcia. Guadeloupe was a big ship, and had been alotted a substantial cargo of sugar, Capeche dyewoods, Purge of Jalapa (a laxative restorative plant found in Mexico), cotton, vanilla, cocoa, plant seedlings, copper, a great quantity of hides, valuable cochineal and indigo for dyes, and most importantly, as many as three hundred chests of silver containing 400,000 pieces-of-eight valued at 613,000 pesos. Among her passengers was the president of Santo Domingo, Hispaniola, as well as a company of prisoners. (Shomette 2007:19)

So writes Shomette in his enlightening tale of a routine Spanish treasure shipment casting its fate to the wind. Another account reports just five ships and names only de Guadeloupe. And according to a TreasureNet™ post by rik, there are as many as eight ships in the armada under Bonilla's command:

The small armada carries important passengers like the Governor of Havana and family, the quartermaster general of Chile and family, a treasure and luxury item shipment of the King's own company, and a silversmith as representative of another precious cargo's owner. They are similarly laden with more Spanish Reales (known as pieces-of-eight), valuable commodities, diamonds, and precious metals, all extracted from the conquest of Central and South America. But it is de Guadeloupe that is the greatest prize, with more than 12 tons of silver in 400,000 pieces-of-eight, each of which weighs one ounce. The early American silver dollar is based upon this coin and its weight / value in silver. That is why 25¢ is known as two bits. Two pieces (or bits) of eight make a quarter. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

The small armada carries important passengers like the Governor of Havana and family, the quartermaster general of Chile and family, a treasure and luxury item shipment of the King's own company, and a silversmith as representative of another precious cargo's owner. They are similarly laden with more Spanish Reales (known as pieces-of-eight), valuable commodities, diamonds, and precious metals, all extracted from the conquest of Central and South America. But it is de Guadeloupe that is the greatest prize, with more than 12 tons of silver in 400,000 pieces-of-eight, each of which weighs one ounce. The early American silver dollar is based upon this coin and its weight / value in silver. That is why 25¢ is known as two bits. Two pieces (or bits) of eight make a quarter. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

The King is anxious for a successful voyage and transit of his goods. These valuables are sorely needed to replenish the Spanish treasurer from years of conflict with England and France, known in Europe as the War of Austrian Succession and, in the colonies as, King George's War. Mother Nature has other plans. This time, Bonilla's own flagship and its precious cargo will be jeopardized by the fierce weather. It will force him to trust a former enemy in a desperate encounter with English privateers turned pirates - including some FitzRandolphs and a young Joseph (Thorne) Jackson of Woodbridge, New Jersey, that are the original subjects of my research.

This story draws from several different accounts of the events retold from personal records and government documents. The Spanish perspective is taken from Bonilla's log and Spanish documents as referenced in Donald Shomette's recent compilation of shipwreck tales. The English and Dutch perspectives are contained in colonial government correspondence and news articles. The Jersey pirates' tale is told by shipmate William Waller in his 1750 testimony to the New Jersey Provincial Justices. The New Englander sloop's story was passed down in the family of one of the ship's owners. But there are also two jokers in the pack, Owen Lloyd and William Blackstock. It is Blackstock, alias William Davidson, who tells their story in his 1750 testimony before Dutch West Indies Justices. He'll also tell us how some of the treasure gets buried on the "real" Treasure Island - and what happens to it next. Be sure to follow the links to learn more about these stories.

Click on a section title below to learn more about the next events in this adventure or open all sections and browse.

On August 18, 1750, Bonilla opts to set sail despite worsening weather. Perhaps he is hoping the weather will stay out of his way or keep pirates at bay. They pass Cape Canaveral at 29° North latitude on the Florida Penninsula by the afternoon of August 25 when the fleet encounters dark skies and blustery winds out of the north. The winds turn to gale force of a shifting direction that batter them from the southwest by evening. A full day later, Los Godos is the first to succumb to the tempest turned hurricane. She takes on more water than her pumps can handle. Then waves finally break her tiller and winds rip her sails. As control is being lost, her captain orders a lightening of the load, with the largest livestock first; then cannon, oven, and damaged boats. She is crippled and temporarily out of sight of the fleet. San Pedro fares much the same. (Shomette, p21)

On August 18, 1750, Bonilla opts to set sail despite worsening weather. Perhaps he is hoping the weather will stay out of his way or keep pirates at bay. They pass Cape Canaveral at 29° North latitude on the Florida Penninsula by the afternoon of August 25 when the fleet encounters dark skies and blustery winds out of the north. The winds turn to gale force of a shifting direction that batter them from the southwest by evening. A full day later, Los Godos is the first to succumb to the tempest turned hurricane. She takes on more water than her pumps can handle. Then waves finally break her tiller and winds rip her sails. As control is being lost, her captain orders a lightening of the load, with the largest livestock first; then cannon, oven, and damaged boats. She is crippled and temporarily out of sight of the fleet. San Pedro fares much the same. (Shomette, p21)

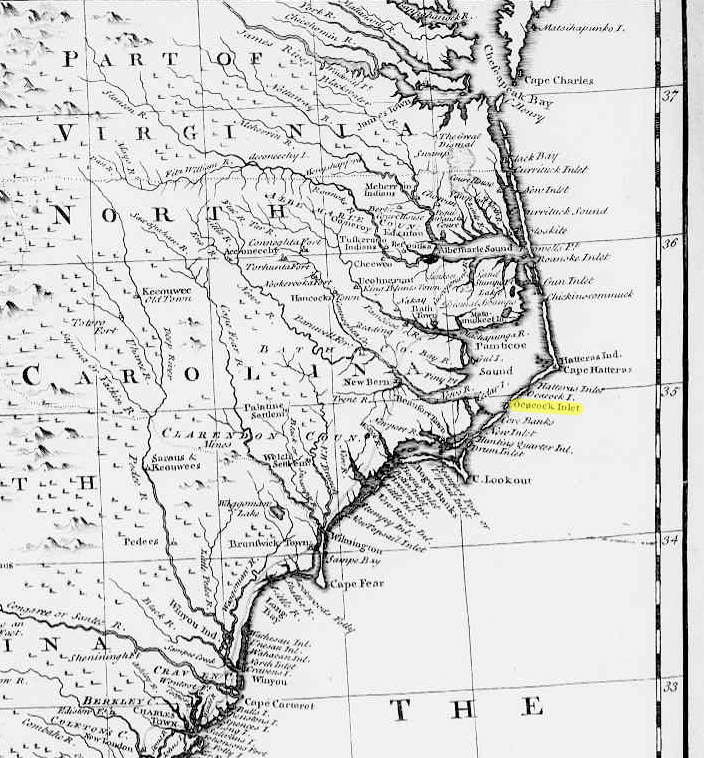

Three days after the first signs of bad weather, on the 28th, Los Godos makes contact with Guadeloupe as the separate ships continue to be battered by wind and waves not far from the Carolina coast. With nightfall, all contact is lost forever. The forces of nature continue to disperse the vessels' paths. Both vessels are driven relentlessly nearer the dangerous shoals of North Carolina's Outer Bank Islands at 33° North. The crews, passengers, and prisoners are left to pray that they do not share the watery fate of the livestock.

On the 29th, El Salvador is the first ship lost, breaking up in the waves on a beach near Topsail Inlet. Only a few crew escape, washed ashore with eleven boxes of the King's own silver. A Bermuda registered sloop captained by Englishmen Ephraim and Robert Gilvert survivies a sandbar to anchor near the wreckage and scavenge it for sails and several chests of treasure. Soledad is lost south of Ocracoke near Drum Inlet, but all the crew and fourteen chests holding 32,000 silver pieces-of-eight survive.

On the 29th, El Salvador is the first ship lost, breaking up in the waves on a beach near Topsail Inlet. Only a few crew escape, washed ashore with eleven boxes of the King's own silver. A Bermuda registered sloop captained by Englishmen Ephraim and Robert Gilvert survivies a sandbar to anchor near the wreckage and scavenge it for sails and several chests of treasure. Soledad is lost south of Ocracoke near Drum Inlet, but all the crew and fourteen chests holding 32,000 silver pieces-of-eight survive.

Guadeloupe stays afloat long enough for the winds to subside on the 30th. Bonilla anchors the broken-masted Admirante of the fleet several leagues south of Cape Hatteras. They weather out the storm tethered there overnight. Bonilla assesses the degraded condition of his vessel the next morning and realizes she needs considerable repairs in the protection of the other side of the perilous Ocracoke Bar. High water and less wind might help the damaged hulk with makeshift sail maneuver to a safer harbor.

But Bonilla risks mutiny of the crew and its leader, boatswain Pedro Rodrigues. They plan to either run the boat aground or throw the treasured goods overboard to ensure passage across the bar. Bonilla holds firm, sending out a scouting party that yields a small boat and pilot to assist them over the bar. Risking exposure to theft but to lighten the load, Bonilla also orders the chests of treasure put ashore using Guadeloupe's pinnace. (Shomette, p24)

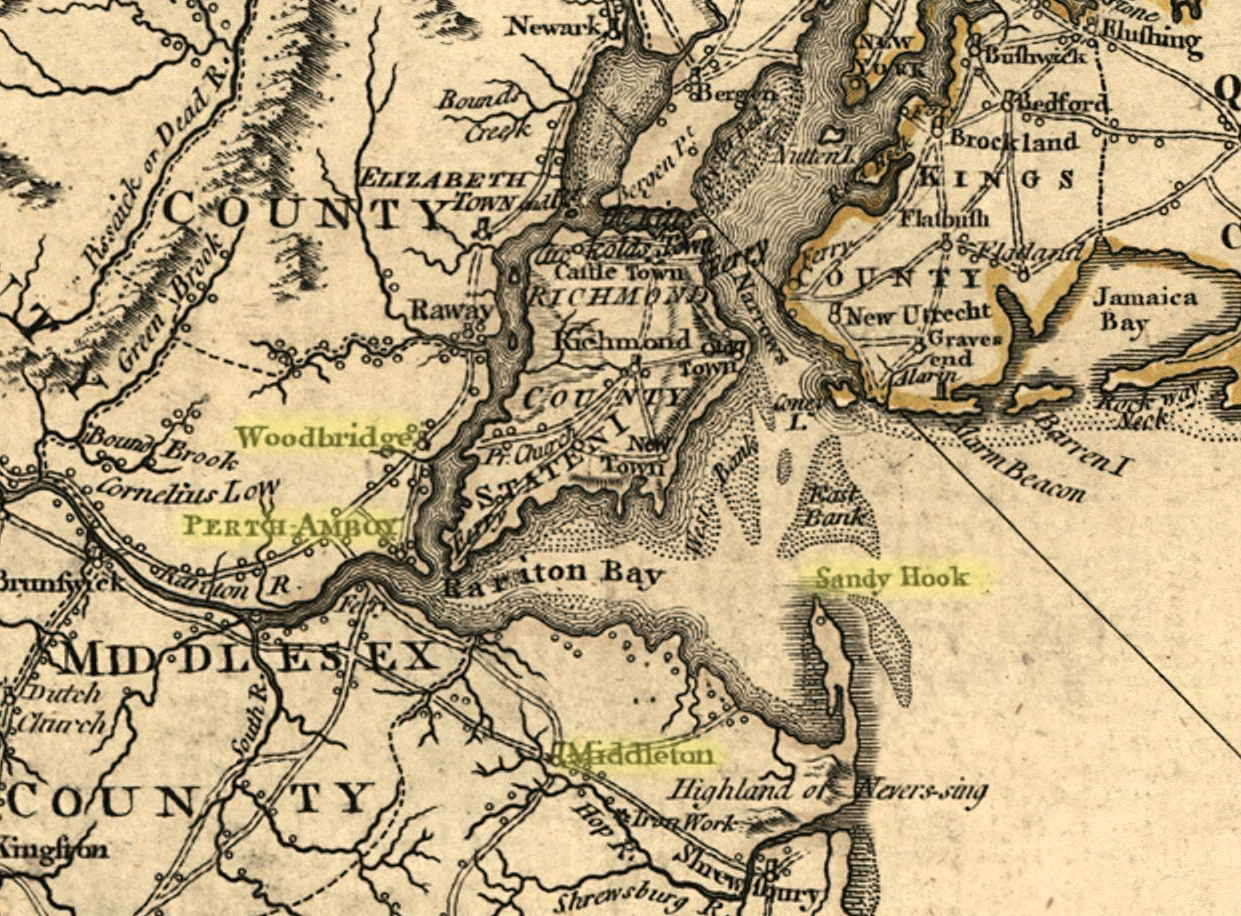

At the same time, but hundreds of miles up the coast in New Jersey, a mariner named William Waller and one Margaret FitzRandolph, both of Woodbridge, take out a marriage license on the 1st of September. (NJ Archives, v22, p147) When the marriage occurs or if there is a honeymoon is not reported. But within three weeks, the groom will depart for the Carolina coast and an unexpected adventure with his new bride's cousins. We will hear more of Waller as the source for much of the New Jersey privateer's perspective in this story.

By the 3rd of September the disabled treasure ship is maneuvered into the modest protection of the bayside of Ocracoke Inlet. (Stick & Stick, p38) Bonilla and some of his crew are ashore the first night when a "Bahamian snow named Carolina appeared on the scene and quietly made fast to the ship." (Shomette, p31) The pirates grab only a few things before being repulsed by the remaining crew, but Bonilla and de Guadeloupe remain awkwardly stranded on the colonial English shore for weeks.

Two weeks later and back up the coast in New Jersey, Samuel Fitz Randolph sets sail from Perth Amboy on September 19 in his sloop, Mary, of Woodbridge. The crew includes Samuel's sons, Kinsey and Samuel Fitz Randolph, Thomas Edwards, Benjamin Moore, Joseph Jackson (born Joseph Thorne), Silas Walker, and William Waller - a newlywed for less than three weeks. The destination and purpose of the voyage is unreported in Waller's later testimony before the Provincial Court Justice Samuel Nevill.

A week later in North Carolina, Governor Gabriel Johnston assembles his Council to get their support in dealing with Bonilla's predicament and the state of affairs it has created on the Outer Banks. The customs officers contend that the Spaniards unlawfully unloaded their cargo on North Carolina soil and should be seized for duties and penalties. The Governor suggests offering assistance and protection even though none has been requested. Colonel Innes, a member of the Council most experienced in the ways and language of the Spaniards, is sent to Ocracoke to investigate the situation and Bonilla's needs.

On the way to Ocracoke, Innes learns that the Bankers, the ungovernably independent inhabitants of the wild and remote island chain, are planning to raid the wrecked Guadelupe "in force" for whatever they can salvage. Upon hearing the news from Innes, Governor Johnston makes an immediate request for reinforcements from South Carolina in the form of the British warship H.M.S. Scorpion. He will seize the Bonilla's vessel to protect it's cargo by force, if necessary. While the provincial governments figure out what to do, some business interests of South Carolina try to bring some action their way from the north. "A man named Tom Wright had come up from Charleston, was mingling with the Spaniards incognito, and was advising them to ignore the government of North Carolina and ship their valuable cargo to Charleston instead." (Stick, pp38-39; Ballance, p15)

Following the storm from the south is a seventy-five ton sloop, Three Sisters, captained by Zebulon Wade. The ship was built as a trader in Cohasset, Massachusetts, by Aaron Pratt, Stephen Stoddard, Israel Whitcomb, and Mrs. Binney. This was a step up in ships for Wade, son of a sea captain and great-grandson of Nicholas Wade, the immigrant that established the Wade family in Scituate 120 years earlier. (Burrage & Stubbs, p1420) Three Sisters is likely on the return leg of her maiden voyage, a "trading run to southern ports." (Wadsworth) The Vice-Governor of the Danish West Indies will later recall seeing the ship in harbor there. (Knight) The Three Sisters destiny will take its crew to Ocracoake Inlet by September 3rd. (Benson) Depending on the timing, they could have witnessed the arrival of the "Bahamian snow named Carolina" and the attack on de Guadelope that night. These accounts are silent on that point.

Waller tells us that when Mary arrives at Ocracoke, they see "a large Spanish Ship of about 500 Ton at an anchor over the Bar" of Ocracoke Inlet. The ship appears to be in distress, having lost the heads of her foremast and main masts. Her mizzen mast and rudder were also gone. (NJ Archives, v16 , p276-280)

Shomette describes the encounter from the Spaniards' perspective. In this version you will find that the Three Sisters is called the Seaflower. It is hard to say which name is correct. Seaflower is taken from a translation of contemporary records, while the name Three Sisters was passed on verbally for a hundred years before being recorded.

At this critical juncture, two bilander sloops appeared on the scene. One was a New Englander called Seaflower, commanded by Zebulon Wade, of Scituate, Massachusetts, the other a New Jerseyman from Perth Amboy named Mary, Samuel FitzRandolph master and owner. Despite the piratical actions of the last English visitors on the scene, and his own fears that the newcomers might play another "scurvy trick," Bonilla guardedly viewed the arrival of the two sloops as an opportunity. The winds remained high and the water quite shoal in the shelterless cove, and his ship might be bilged at any worsening of the weather. With "the Intrigues and Artifices of Pedro Rodriguez Boatswain having got most of the Men on His side and under Pretence of going to Virginia," there seemed little choice. Calling his remaining loyalists together for a conference, the admiral proposed employing the two shallow-draft sloops "to keep his money and other effects on board, 'till he could either hire or buy another ship." It was so agreed. For some reason, perhaps to curry his favor, Rodriguez was sent aboard Mary to negotiate an arrangement to carry the cargo to Norfolk. One of FitzRandolph's crew, William Waller, of Woodbridge, New Jersey, served as interpreter. Within a short time, Mary's master had agreed to transport the lading to Virginia for a fee of 570 pieces-of-eight. A similar agreement was made with the master of Seaflower. Soon afterward the Spaniard returned with fifteen hands in a launch to haul the two sloops alongside Guadeloupe.

On or about October 5, as the transfer of treasure was under way, a certain Colonel Innes arrived bearing a letter from Governor Johnston, summoning Bonilla to New Bern to answer charges of illegally breaking bulk in the colony without permission. Bonilla, who had been expecting assistance, not a summons, was stunned. Fortunately, having also been sent to specifically inquire into Guadeloupe's situation, the Colonel was not unsympathetic to the Spaniard's plight. He had become immediately suspicious of the intentions of Mary and Seaflower and expressed his fears to Bonilla that the sloops would attempt to run away with the treasure. He even volunteered to take possession of them. In the meantime, a sloop-of-war might be provided for the purpose of carrying the money to safety. But to do so, it would be necessary for Bonilla to accompany him to meet with the governor. The Spaniard readily accepted. Rodriguez, however, now backed by many of the remaining crew and fearing that if the English got their hands on the treasure neither he or his men would ever be paid, vehementally protested and "would not suffer the Money to be removed." Nevertheless, Bonilla set off immediately with the colonel.

Fifty-five chests of treasure and a "substantial cargo of cocoa, cochineal, and sugar" had already been transferred to Seaflower and upward of 54 chests to Mary. Bonilla halts the loading operation and secures his goods in preparation for his absence. He issues written instructions "to have the two vessels' sails carried ashore where they would be guarded until his return, for without sails the two sloops could not possibly leave. Then he ordered ten loyal armed men placed aboard each vessel to prevent any underhanded actions. The holds of both vessels in which the treasure chests had been stowed were to be barred, locked, and kept under constant guard." (Shomette, p18)

While Bonilla was making arrangements for the protection of the King's treasure, on shore some privateers are scheming how nice it would be to take it for themselves. They are frequent travelers in the waters between the Carolinas and Carribean commonly known as the Bermuda Triangle. First they observe the stranded galleon, then the arrival of the sloops. But it is the effort to preserve the large ship's cargo that gets their attention fixed upon the galleon. Knight describes the scene for us.

William Blackstock, who also went by the name of William Davidson, was born in Dumfries, Scotland. A mariner by trade, he had sailed out of Rhode Island at the end of September, 1750, and put in at the Ocracoke Inlet on or about the 1st of October. ...

When Owen Lloyd first approached him with a proposition to steal-away with the two sloops, Blackstock made light of the subject and passed Lloyd off as an idle schemer. But, with the departure of the Spanish captain for New Bern, it became clear that Lloyd and his associates had resolved to make good their plan. Upon consideration, Blackstock gave in to Lloyd’s urgings and joined the plot. The conspirators were a hastily-assembled collection of salt-encrusted rabble from up and down the Eastern Seaboard. Among them was Trevet, a thickset Carolinian with a slow back-county drawl, who Lloyd had chosen as mate. And then there was James Moorehouse of Connecticut, a headstrong young Yankee; William Dames, a sharp-eyed Virginian; a shoeless old sea-dog by the name of Charles; and Owen Lloyd’s brother, Thomas, who at the stump of one knee wore a crudely fashioned wooden peg.

Coincidental to this plotting and the salvaging of the Guadelupe's cargo on October 5, 1750, England and Spain sign the Treaty of Madrid, formally ending 11 years of hostility. Yet to be ratified, it will be eight months before the Treaty will be announced to the Colonies with a copy published in a Philadelphia newspaper. (Baynes, p743; Collections v.10, p.271) That treaty sets an expectation of mutual respect and cooperation between the English and Spanish. It specifically details these expectations in cases of piracy since a catalyst in 1738 for starting the war was English outrage over Spanish piracy. Captain Robert Jenkins reported to the British House of Commons how Spanish Coast Guards boarded and pillaged his ship and abused his person. Upon holding up his amputated ear as evidence, the conflict also became known as the War of Jenkins' Ear. (Britannica) It would seem this cause is not the motivation of Owen Lloyd and William Blackstock, however.

After the treasure was loaded on FitzRandolph's sloop, Mary, "the hatches of the sloop going into the hold were barred and locked by the Spaniards; and the said Spaniards took the keys away with them." Master Samuel FitzRandolph and his two sons, Kinsey and Samuel, stay aboard Mary while Waller and the rest of the crew go for water. When they return, Kinsey tells Waller that he had been in the hold and had gotten 700 pieces-of-eight for his father and 40 pieces for himself. Furthermore, Kinsey and Thomas Edwards cut a hole at the foot of the larboard cabin, through the bulkhead, and into the hold. Money is taken out of the hold twice before they are done. Twice the crew divide the silver pieces amongst themselves.

After the treasure was loaded on FitzRandolph's sloop, Mary, "the hatches of the sloop going into the hold were barred and locked by the Spaniards; and the said Spaniards took the keys away with them." Master Samuel FitzRandolph and his two sons, Kinsey and Samuel, stay aboard Mary while Waller and the rest of the crew go for water. When they return, Kinsey tells Waller that he had been in the hold and had gotten 700 pieces-of-eight for his father and 40 pieces for himself. Furthermore, Kinsey and Thomas Edwards cut a hole at the foot of the larboard cabin, through the bulkhead, and into the hold. Money is taken out of the hold twice before they are done. Twice the crew divide the silver pieces amongst themselves.

Later, crewman Joseph Jackson gives Waller about "450 pieces-of-eight tied up in an oznabrig bag" and "a letter directed to his [step]father, James Jackson, in Woodbridge", New Jersey. Joseph instructs Waller to deliver 213 pieces-of-eight to James Jackson and the remainder Waller keeps as his share. A few days more, Master Samuel & Waller "had words" and part by mutual consent. Waller then goes aboard a sloop riding in the harbour, captained by a Master Anderson. It soon sets sail for Middletown in New Jersey, Waller's home. After they pass the bar at Ocracoke Inlet, Anderson discovers that Waller has Spanish money on board and tells him that "if he had known it before, he would not have brought him." (NJ Archives, v16 , p277-280)

When Mary's master returns to the ship from shore, he probably does not tell Waller of his plans with Lloyd, Blackstock, and Wade. If so, Waller would likely have included some reference to new crew members coming aboard with him. As it is, the boarding of Owen Lloyd's brother, Thomas, and some of the "seaworthy" rabble collected ashore should have been well noticed and questioned by the crew that sailed together out of Perth Amboy a few weeks earlier.

The plan with which FitzRandolph and Wade agree has the two shipmasters hiding below deck when the Lloyd brothers and their men make it look as though they commandeer the two sloops and make off with the cargo. Blackstock will pilot Seaflower with Owen Lloyd in command and Thomas Lloyd will maneuver Mary. Once away, they will sail to the West Indies and bury the treasure on an island well known to the scheming Lloyd. The peglegged Thomas was likely unaware of the damage to the hull by the crews pilfering, but their fate is likely sealed by those earlier actions. (Knight)

Shomette describes the next piratical events as they unfold before the stunned Spaniards.

... the seamen's escapades palled by comparison to a cabal hatched between Captain Wade, Captain FitzRandolph, and one Owen Lloyd, who "had armed themselves for that purpose, to run away with what was put on board their vessels."

True to form, Pedro Rodriguez proved as untrustworthy as ever and may have even been a partner to the larcenous conspiracy that ensued. Whatever his later excuses may have been, he had neglected to remove the sails of at least one, and possibly both, of the bilanders and had posted no guard onboard Guadeloupe. On October 9, with Bonilla far away, and a fresh, fair wind blowing, the English pirates, led by Owen Lloyd, put their plan into action. About noon and without warning, the two vessels cut their cables and put out to sea. The astonished Spaniards immediately took up pursuit in a longboat, firing their guns as they scuttled along like an elongated waterbug. Seaflower, commanded in the action by one William Blackstock, alias William Davidson, and navigated by Lloyd, nevertheless successfully carried off "55 chests of money, some trunks of gold and silver wrought plate, and 155 bales of conchineal and other things." Though described as a "dull Sailor" and carrying no more than ten men aboard, and soon also pursued by the Guadeloupe's pinnace, the pirate sloop made a clean escape over the bar and sailed away for the West Indies. FitzRandolph's sloop, however, had the misfortune of missing stays and, perhaps slowed in the escape by the plugged hole in her side cut by the crew, ran aground in the roads. She was quickly boarded and captured by a launch from Guadeloupe. On learning of the piracy, Bonilla was devastated. "I fell very ill of shock," he morosely informed the Marquis de la Ensenada, "and nearly died. I am very weak and in ill health now." He placed the blame for the affair squarely on Rodriguez, who with fifty men under his command had failed to stop the slow sailing Seaflower and had succeeded in taking Mary only because it ran aground.

The Sticks give us a Carolina perspective.

By the time H.M.S. Scorpion arrived from Charleston, Bonilla was so concerned over his mutinous crew, the disappearance of the treasure laden sloops, and the prospect of bad weather that he petitioned Governor Johnston to direct the Scorpion to transport the balance of the cargo to Europe. Governor Johnston agreed to this, but at the same time he presented Bonilla with a claim for salvage and promptly commandeered something over 16,000 dollars for his trouble, though the British government forced him to give it back some time later.

So Captain Bonilla finally left the Banks and returned to Cadiz, but with less than half of the cargo and specie which had been aboard the vessel when she entered Ocracoke Inlet. And the residents of the Banks, having been hemmed in from all sides as these various intrigues were in progress, probably were as glad to be rid of this group of Spaniards as they were when the crew of the "large black sloop" had departed nine years earlier, after burning the tents on Ocracoke.

Wadsworth relies on an account of the events passed down in the Aaron Pratt family, one of the owners of the New Englander sloop. In this version, the ship is named Three Sisters rather than Seaflower. The master is the same Zebulon Wade, who conspires with FitzRandolph to run off with their cargoes. The sloops are to head for the West Indies and bury the booty in the sand. With Mary running aground, Three Sisters proceeds alone to Statia, now St. Eustacius in the Netherlands Antilles - a Dutch colony - to bury the treasure. There will be more on that later.

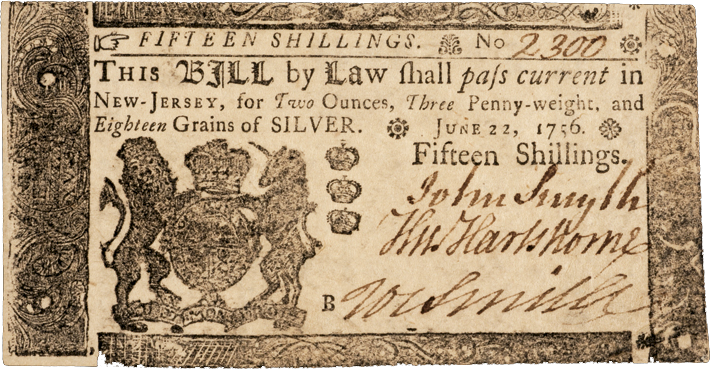

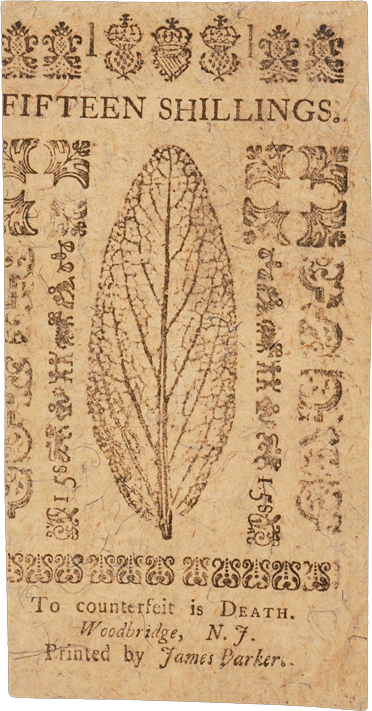

By Friday, October 16th, Master Anderson's sloop with Waller aboard arrives at Sandy Hook. There, Waller goes aboard a sloop belonging to James Smith, Esquire, of Woodbridge. Note that two of Smith's kin sign the Jersey money in those days (see image below).

By Friday, October 16th, Master Anderson's sloop with Waller aboard arrives at Sandy Hook. There, Waller goes aboard a sloop belonging to James Smith, Esquire, of Woodbridge. Note that two of Smith's kin sign the Jersey money in those days (see image below).

The next morning Waller sends for "Mary Jackson junior the [step]sister of Joseph Jackson" and daughter of Mary (FitzRandolph) Jackson. He gives the young Mary six pieces-of-eight and the letter directed to their stepfather, James Jackson.

On Monday night, the 19th, he meets Mary junior again. This time she is accompanied by her mother, Mary, second wife of James; and her mother's brothers, Robert and Hartshorne FitzRandolph (their uncle, William, also signs the colonial paper money - see image below); and their sister-in-law, Mercy Smith. Waller gives Mary junior 207 pieces-of-eight more. Hartshorne FitzRandolph becomes security until the money "should be demanded." So 213 Spanish dollars end up in the hands of Hartshorne FitzRandolph on behalf of Woodbridge tavernkeeper, James Jackson. (NJ Archives, v16, p280; NJ Archives, v12, p520)

Waller also accounts for 129 of the 237 pieces-of-eight he has from the sloop's hold. He testifies later that he "laid out at New York 68 pieces." He lends James Coddington 25 pieces, James Pike 13 pieces, Robert FitzRandolph five pieces, and Isaac FitzRandolph three pieces. He exchanges 15 pieces for Jersey money. The remainder is "now at the deponents place of abode," the house of Robert FitzRandolph.

Waller also accounts for 129 of the 237 pieces-of-eight he has from the sloop's hold. He testifies later that he "laid out at New York 68 pieces." He lends James Coddington 25 pieces, James Pike 13 pieces, Robert FitzRandolph five pieces, and Isaac FitzRandolph three pieces. He exchanges 15 pieces for Jersey money. The remainder is "now at the deponents place of abode," the house of Robert FitzRandolph.

Then there are 108 Spanish dollars in Waller's possession as he resides at Robert FitzRandolph's house. (NJ Archives, v16, p277-280) That makes a total of 321 Spanish dollars still in the possession of the "Jersey pirates."

I suspect Waller is residing at this location because of a close family relationship between Robert and Waller's bride, Margaret FitzRandolph. I have not yet ascertained Margaret's relationship to the FitzRandolph family, because it may have been through a previous marriage. I do notice that Waller was reported above to be a resident of Middletown yet was residing with Robert, who has a very young daughter also named Margaret. Since there are no other Margaret's on the record in close relation to Robert's immediate family, I wonder if Waller's wife may yet be young Margaret's namesake.

During this time in the Virgin Islands, as Knight relays to us from Blackstock's testimony, the Seaflower slips into a cove on Norman Island, probably The Bight, as shown on the map. Its coves and caves make it perfect for burying treasure and the model for Robert Louis Stevenson's pirate tale Treasure Island.

During this time in the Virgin Islands, as Knight relays to us from Blackstock's testimony, the Seaflower slips into a cove on Norman Island, probably The Bight, as shown on the map. Its coves and caves make it perfect for burying treasure and the model for Robert Louis Stevenson's pirate tale Treasure Island.

Wade, Lloyd, Blackstock, Dames and eight more crewmen unload "sixty bundles of moldy tobacco", "seventeen bags of indigo", and "one hundred and twenty bale of cochineal, each weighing some two hundred and thirty pounds". That left "a tight-packed stack of heavy wooden crates" for the crew to inspect. There are 52 chests in all. Fifty are uniformly sized and two are taller and wider measuring three feet by two feet, and one-and-a-half-feet deep.

They pry off the lid of one of the many chests to reveal three compartments, each containing a large oznabrig sack sealed with lead. Each bag contains "one thousand freshly-struck, eight-reales coins" - pieces-of-eight. The two larger crates are "filled with 'church plate' and other wrought silver." These are religious items decorated with icons and, sometimes, encrusted with jewels.

The pirates divide up the pieces-of-eight with five chests each to Lloyd and Wade; four chests go to each of the other 10 men. The church plate and dyes are split into twelve roughly even shares. Nearly all the pirates bury their share of coins and silver plate ashore. Each hiding their treasure out of sight of the open beach back into the trees and underbrush. "Lloyd and Captain Wade each kept one chest of coins on board and buried the rest. Blackstock and William Dames resolved to leave the ship at their first opportunity and were the only ones to remove all of their booty (silver and goods) to shore."

The men return to the beach late in the afternoon to witness a fisherman, Thomas Walts, push off from alongside their sloop and head for the far north end of the cove. Lloyd leaves Blackstock, Dames and old Charles ashore with the treasure, and departs in the sloop with the rest of the crew and goods. The marooned sailors soon realize they are without food and water and so hail the fisherman for help. Blackstock and Dames get a ride in the fishing boat to the larger, nearby island of Tortola, leaving Charles to watch the situation on Norman Island.

At Tortola, Blackstock reports his situation to the island council president, Abraham Chalwell, without mentioning the chests of silver. Chalwell decides to go to Norman Island the next day to inspect the goods and check out Blackstock's story. President Chalwell, Blackstock and Dames arrive at the Bight late the next morning to find dozens of sailboats and smaller craft dotting the cove's shoreline and beach. As they approach the southern beachfront where the goods are piled, Blackstock notices Charles motioning wildly and yelling that their chests of silver have been discovered. So Blackstock directs Chalwell's attention to the bales of cochineal while Dames gets old Charles under control before he says any more about chests.

After Chalwell decides that Blackstock's story has merit, the two head for Dames and Charles position in some shade on the north shore. At first encounter, Chalwell demands of Charles "if there is any money here bring it out. If you do, I will take care of it for you. Otherwise, I will leave you here and let these people take your life for it." The council president must have been an effective leader and interrogator as Charles then produced "six bags of silver coins" from "a rock crevasse not far from the tobacco pile." The group returned to Tortula that afternoon. (Knight)

On the following morning, a shallop belonging to one Captain Purser of St. Christopher arrived at Tortola and President Chalwell made quick use of it to bring the cochineal over from Norman Island. Along with the dyestuff, the ship also brought three more bags of coins that Charles claimed to have "met" while loading the bales.

True to his word, Chalwell handed all of the recovered goods over to Blackstock, retaining only two bales of cochineal as a "present" Blackstock then gave one bale of cochineal to the "collector of the port", another to Thomas Walts for the service of his cobble, and yet another to Captain Purser for freight on the shallop. The remaining fifteen bales of cochineal and nine bags of coins, plus a handkerchief containing about four or five hundred coins, were divided equally between Blackstock, Dames and Charles. Additionally, Blackstock and Dames each kept their one-bag share of indigo, as Charles had left his aboard the sloop. Later, Charles and Dames sold their cochineal to John Pickering, Esquire, for one thousand pounds currency per bale, while the “collector” purchased Dames’ indigo. (Knight)

About two weeks after Waller delivers James Jackson's share to his family in Woodbridge, the 46 year old James dies, suggesting that James may have been too ill to receive the money in person on the 19th. The NJ Calendar of Wills provides an account of the estate of "James Jackson, yeoman." His widow, Mary, and her brother, Hartshorne FitzRandolph are administrators on the estate. Richard FitzRandolph is fellow bondsman. The inventory made by Sam Moores and Abram Tappan assesses the estate value at £80.4. The Memorandum of bonds, bills and book debts dated November 7, 1750, lists 289 local male residents that probably had accounts due to James' tavern operation. (NJ Archives, v30, p260)

About two weeks after Waller delivers James Jackson's share to his family in Woodbridge, the 46 year old James dies, suggesting that James may have been too ill to receive the money in person on the 19th. The NJ Calendar of Wills provides an account of the estate of "James Jackson, yeoman." His widow, Mary, and her brother, Hartshorne FitzRandolph are administrators on the estate. Richard FitzRandolph is fellow bondsman. The inventory made by Sam Moores and Abram Tappan assesses the estate value at £80.4. The Memorandum of bonds, bills and book debts dated November 7, 1750, lists 289 local male residents that probably had accounts due to James' tavern operation. (NJ Archives, v30, p260)

Among the many debtors are familiar Woodbridge family names. Surnames listed more than once in order of frequency include eight each named Bloomfield or Moore[s]; six named Alston, Dunham, [Fitz] Randolph, Inslee, Kelly, or Thorpe; five with surnames Bishop, Bunn, Shotwell, or Walker; four named Freeman, Morris, Smith, or Thompson; three each with names Conger, Cutter, Davis, Jones, Kinsey, Martin, Pike, Reynolds, or Wheaton; and two each named Arvine, Ayres, Brown, Brooks, Bird, Clarkson, Condict, Crowell, Daniels, Davi[d]son, Force, Ford, Herod, Harriman, Horner, Jackson, Johnson, Kearny, Kent, MacLachlin, Pack, Pangborn, Parker, Potter, Robinson, Ross, Sharp, Thornell, and Vale. In thirty years, these names will feature prominently in the War for Independence as many descendents of these citizens will be Patriots serving at all levels and in all ways.

Listed of special interest to our story are Samuel [Fitz]Randolph Jr, Sylas Walker, and Benjamin Moore of Mary's crew. There are also John Waller, keeper of the Perth Amboy Jail; James Nevill, likely kin of the Provincial Supreme Court Justice; and Zebulon Pike, great grandfather to the adventurous Colonel of the same name. Altogether, it would seem that James Jackson is a well-known member of the community.

On November 5, just two days after James' death and before this inventory of the estate, William Waller testifies before Judge Samuel Nevill, Esq. and James Smith, Esq. Master Samuel Fitz Randolph, Kinsey Fitz Randolph, Benjamin Moore, and Silas Walker are also deposed. As Mary's owner and master, Samuel Sr. also petitions for the Governor's guidance on the disposition of the stolen money. (NJ Archives, v16 , p277-280)

It is also the start of November 1750 when Blackstock returns to Norman Island with the fisherman, Thomas Walts, to find that his share of church plate has been stolen. Word had spread and the locals proved just as opportunistic as the pirates. The council president's son is said to have retrieved "at least twenty bags of Spanish coins", the island marshall got 30 bags, and yet another is said to have found "a considerable quantity of 'plate'". Fearing a total loss, Blackstock and Dames use 1,000 Reales to buy Purser's boat but are denied permission to embark with their share of the goods until the council has considered the matter.

Nearly a week passes before the council decides that Blackstock and Dames can leave, but only after selling their cochineal and indigo to local interests. Knight describes for us the final fate of Lloyd, Blackstock, and their crew.

On the 14th of November, Blackstock and Dames finally set out from the British Virgins with Captain Purser and a Mr. Young as passengers, and an old Tortola "Negro" as crew. Although the ship's papers gave her destination as North Carolina, the shallop headed first for St. Eustatius, where Purser and Young disembarked. There, while lying off the road at Oranjestad, Blackstock caught wind that Owen Lloyd had been apprehended and at that very moment was a prisoner in the island’s fort. From what little straight talk they could muster, Blackstock and Dames pieced together that after leaving Norman Island Lloyd and the crew had sailed directly to the Danish-held island of St. Thomas. There, the men sold off the cargo and abandoned the sloop, making a pact to never associate with one-another again. Soon after, Lloyd purchased another sloop and set out for the Leeward Islands, but word of his misdeeds preceded him. He had been immediately arrested upon setting foot on St. Eustatius.

The story of Owen Lloyd's capture, as told to Blackstock and Dames by a loose-lipped Mulatto with one blue eye, was made even more troubling by the informant’s repeated references to Lloyd as, "a villainous pirate." It was then that the two decided to go their separate ways. Dames, who longed for cooler waters, had a mind to take the first available berth on a northbound schooner and leave the West Indies in his wake; while Blackstock was reasonably sure that with legal title to the shallop, and a proper sea-pass from President Chalwell, he had a fair chance of steering clear of any trouble. That was, of course, as long as Owen Lloyd hadn’t given any names. With this resolve, Blackstock handed over to Dames four hundred and fifty pieces-of-eight for his one-half part in the shallop, and ordered the old “Tortola Negro” hand to put the homesick Virginian ashore.

By evening the shallop was driving hard under a full press of sail, the island of St. Martin off her starboard bow. His shoulder braced against the wheel, Blackstock gazed out into the setting sun "Nowhere on Gods own earth," he declared only to himself, "do Satin's fires battle so hard to consume the day."

Before another night had passed, William Blackstock languished in chains: the unwilling guest of the Honorable Governor Gumbs of Anguilla. And as to the whereabouts of Dames, or any other members of the sloop's crew, he really couldn’t say.

Wadsworth relates that Wade returns home on a another ship sent by Mrs. Binney, one of the owners of Three Sisters. That ship and the rest of its cargo is left with the Dutch - a total loss on her maiden tour.

The theft so soon after the war creates a stir among the English colonists, the Spanish, and the colonial Governors, alike. The following item announcing the encounter, is published November 15, 1750, in The Pennsylvania Gazette with a New York dateline. It attests to fear among some that this piracy will leave fellow Englishmen vulnerable to similar mistreatment. (Poff)

NEW-YORK, Nov. 12.

By a Vessel from North-Carolina, we have a melancholy Account, that two English Sloops having been hired there by the Spaniards to carry the Money saved out of one of the Galleons lately lost near Ocacock Bar, to Virginia; they took their Opportunity to make off with the Treasure, while all the Spaniards were ashore; one of the Sloops got clear off, but the other missing Stays, run ashore, and was recovered by the Spaniards:—It is much feared the Master and Mariners will meet with condign Punishment, besides bringing a lasting Infamy on the British Nation, for their Treachery to People in Distress;—and give the Spaniards a Plea for using poor Englishmen ill, that may have the Misfortune to fall into their Hands. They will doubtless think they ought to have Justice done them; notwithstanding if any of our Vessels from the Bay happen to be lost on their Coast, or put into their Ports in Distress, they not only seize the Vessel and Cargo, but make the Men Prisoners; altho’ they have in Nature no more Right to the Wood in the Bay, than the English have to the Mines in Mexico. Their Depredations and Captures on the High Seas by their Guarda Costas, is a Piece of Villainy, little inferior to this Robbery; tho’ tamely suffered by us, who are near becoming the Dupes of all Nations.

Economic issues were also unresolved. Shomette (p38) observes that Guadelope's owner likely follows a lead on the money stolen by the other sloop, Seaflower. At about the same time, he is reported making inquiries in the Boston area.

In mid-November, it was reported in Boston that a mysterious, unnamed "Spanish gentleman belonging to a large and rich ship of his nation" lately cast away on the Carolina coast, possibly Respaldizar, was in town attempting to locate and retrieve $150,000 in silver coin and other effects, including $100,000 worth of cochineal, purloined from the wreck of the Guadeloupe by Zebulon Wade's sloop Seaflower, which was believed to be in new England. Bostonians were anything but positive about the Spaniard's chances. "But we dare not promise," wrote one newspaper editor, "upon the skill in Astrology as to predict that all the money, &c. will be recovered, and that the master and his accomplices will be apprehended. For a man with such a number of dollars about him, may be said to have powerful hands."

It also appears that not everyone is as convinced as Blackstock and Dames that all the loot buried on "Treasure Island" has been discovered. Singer points out that "The book Lagooned in the Virgin Islands by H. B. Eadie mentions a letter dated December 22, 1750 which refers to 'trouble-some Spaniards infesting the seas around the Virgin Islands' and their recovery of part of the loot from the caravel Nuestra Señora which had been buried at Norman Island."

On New Year's Eve, the New Jersey Governor acknowledges the arrest and escape of William Waller. From his home in Burlington, Jonathan Belcher writes a note of congratulations to Judge Nevill on his efforts. He also informs Nevill that he heard that Elizabeth Waller, the jail keeper's wife, was bribed for her assistance in Waller's escape. Belcher writes that the sheriff will be held accountable and adds that he will present the whole affair before his council. (Collections v.10, p.265; NJ Archives s1 v16, p244) It would seem that Waller was detained immediately after his testimony/confession in early November. If so, the newlywed mariner has had less than those weeks before setting sail to spend with his bride.

The Duke of Bedford writes the Governor Belcher on 10 January, 1751, "relating to the Spanish Wreck Lost last fall on the Coast of North Carolina." He desires the opinion of the Governor's Council regarding the incident. The Duke follows that on February 1 with a copy of the Treaty with Spain. (NJ Archives s1 v16, p308) Seven days later, Governor Belcher presents the judge's reports and testimony of the crew to his Council, asking for their opinion. Council members present at that Burlington session are Misters Reading, Alexander, Rodman, Johnston, Kemble, and Saltzar. (NJ Archives, v16 , p277-280)

The Council later interviews the examiners, prepare their reply on the 17th, and present their findings the next day in another session at Burlington. In attendance are the Governor and Council as listed before except for the presence of Mr. Hude and absence of Mr. Kemble. Charles Read is again Secretary to the Governor's Council. They present their opinion as follows. (NJ Archives s1 v16, p282)

We beg leave humbly to report to your Excellency that we have considered the said papers and sent for Samuel Nevill together with James Smith Esquire of Woodbridge before whom the said Depositions were taken & examined them as what further they heard or know Concerning the matters in the papers aforesaid and upon the whole are of Opinion that there is great Reason to Suspect every one of the mariners on Board the said Sloop to have been Guilty of Robbery and Piracy and some to suspect even the Petitioner, and Therefore that the prayer of the Petitioner be not granted.

But on the Contrary, That your Excellency should give order to ye Judges of the Supreme Court or one of them to Cause the Master & Mariners of the said Sloop to be apprehended & brought before them or him, and that they be Separately & privately Examined Concerning the Piracy and Robbery aforesaid and that care be taken that neither of them have any opportunity to Confer with one another from the beginning of the said Examination till it be finished and particularly how they came away from Carolina, for what reason was the said Sloop seized there, what proceedings had been there against them & the said Sloop, and whatever further Questions may be thought necessary for the Discovery of the Truth; And if upon the papers referred to us, and from what shall be discovered by the Examinations, it shall appear that there is sufficient reason to suspect thye said master & Mariners or either of them to have been Guilty of Piracy & Robbery or either of them that then they be Committed till Delivered by due Course of law: And that in the meantime the pieces of eight Confessed by the said William Waller to have been taken out of the Hold of the said Sloop, after they had been Laden therein by the Spaniards together with the Proceeds of the Effects bought by him with such pieces of Eight be Secured in the hands of Andrew Johnston Esquire His Majesty's Receiver General & Treasurer of the Eastern Division of New Jersey until further Order, and that the utmost Secrecy be Observed in this matter until the said Suspected Criminals be Apprehended.

It takes just six weeks to bring some (or all) of the crew to justice. The following news item appears in The New York Gasette Revived in the Weekly Post Boy. (NJ Archives v19, pp.66-67) A few weeks later, on May 2, 1751, the same report appears in the Virginia Gazette. (Poff)

New York, April 8. We have intelligence from the Jersies, that some Men who belonged to one of the Vessels that attempted to carry off some of the Money belonging to the Spanish Wrecks at Ocacock in North Carolina: were last Week apprehended, and committed to Amboy Jail, as 'tis said, by Orders from the Government.

During those six weeks, the Prince of Wales dies, paving the way for his son to become King George III in another nine years. Also, on April 20, Governor Belcher informs the Duke of Bedford that he has dissolved and reformed the New Jersey Assembly. He also informs Bedford that Waller had been jailed and then escaped, and that 317 pieces-of-eight were recovered. The money is being kept in the Provincial Treasury. (Collections v.10 p.269) Not until May 30, does Belcher present to his new council the Duke's last three letters (1) asking council's opinion, (2) conveying the Treaty with Spain, and (3) the announcement of the Prince's passing. (NJ Archives s1 v16, p308)

During those six weeks, the Prince of Wales dies, paving the way for his son to become King George III in another nine years. Also, on April 20, Governor Belcher informs the Duke of Bedford that he has dissolved and reformed the New Jersey Assembly. He also informs Bedford that Waller had been jailed and then escaped, and that 317 pieces-of-eight were recovered. The money is being kept in the Provincial Treasury. (Collections v.10 p.269) Not until May 30, does Belcher present to his new council the Duke's last three letters (1) asking council's opinion, (2) conveying the Treaty with Spain, and (3) the announcement of the Prince's passing. (NJ Archives s1 v16, p308)

Here the Governor accounts for 317 of the coins, indicating that Waller and the Fitz Randolphs turned over all but four pieces. Therefore, it is most likely that the long list of debts to James Jackson's estate are in fact business accounts and not the distribution of these silver coins to his family, friends, and neighbors, as coincidence might suggest. (NJ Archives, v30, p260) It may well be that James' family are also having difficult financial times as evidenced by his attempt to sell the tavern in March 1749. (NJ Archives, v12, p520) There may have been lots of unpaid bar tabs and maybe a serious illness. This would explain Joseph's interest in sending his share of the pirated booty back home at the first opportunity and James not being there to receive it.

On June 7, 1751, at Perth Amboy, Governor Belcher writes two letters of similar purpose. The available summaries do not mention Waller's escape several months earlier. One, to the Duke of Bedford, acknowledges the receipt of a copy of the Treaty with Spain, signed 5th October preceding, which he has published in one of the papers of Pennsylvania for the better information of the people of New Jersey. He also informs the Duke that of circumstances connected with the shipwreck of Bonilla's vessel on the coast of North Carolina, the subsequent stranding of Mary, with some of the Spanish cargo onboard with the 317 coins mentioned in the April 20 despatch and presumed to have come from Mary.

The second such letter of June 7, is sent to the Secretary of State, the Earl of Holderness. In it he reports ordering the Treaty to be published in one of the public news prints in Pennsylvania; assures the Secretary that the affair of Don Manuel de Bonilla shall be attended to and the 317 dollars seized are now in the Treasury of New Jersey. In this letter he adds a report that the ship which escaped with Don Manuel's 55 chests of dollars arrived at the Island of St. Thomas and, there, the captain "put himself under the protection of the Danish Government." (Collections v.10, p.271)

On July 1, Belcher now refers to Bonilla's vessel as "lost." He dutifully reports to the Duke of Bedford that the escapee, Waller, has been recaptured and awaits trial. (NJ Archives v7, pp598-600)

On February 12, 1752, in Perth Amboy, and eleven months after their capture is reported in the news, Nevill presents to the Governor and Council an August appeal from the pirates for release from jail. They argue that there have been no charges or trial for six months and they should be released according to the Habeas Corpus Act. The Council advises the Governor that Judge Nevill proceed as he thinks appropriate. Council members present this time are James Alexander, James Hude, Andrew Johnston, Peter Kemble, and David Ogden. (NJ Archives v16, p370)

In Elizabethtown on November 28 of the following year, Governor Belcher writes to the Secretary of State "desiring orders from His Majesty how the money brought into New Jersey from North Carolina, supposed to belong to the subjects of Spain, is to be disposed of." (NJ Archives v10, p302) The Governor's papers retained in the New Jersey Archive do not include any further correspondence regarding the acts of piracy committed against Bonilla and his vessel. The Archives do not report any further official documents regarding the fate of Mary's master and crew.

Not long after the commotion at Ocracoke Inlet, concrete steps are taken to protect it and provide suitable facilities for a port of entry. In 1753 an act is passed by the North Carolina Assembly for "laying out a Town on Core Banks, near Ocacock Inlet, in Carteret County, and for appointing Commissioners for completing the Fort at or near the same place." (Stick, pp38-40)

We do know that Waller is known as a stage-boat operator just two years after the crew petitions for freedom. A 1753 advertisement describes a stage/ferry passenger service between New York City and Philadelphia. (Roll)

A commodious stage-boat will attend at City Hall slip near the Half Moon battery, to receive goods and passengers, on Saturdays and Wednesdays, and on Mondays and Thursdays will set out for Perth Amboy Ferry; there a stage-wagon will receive them and set out on Tuesdays and Fridays in the morning, and carry them to Cranberry, and then the same day, with fresh horses to Burlington, where a stage-boat receives them, and immediately sets out for Philadelphia.

The term "commodious" is used to indicate an improvement over the smaller, keel-less, open scows that once left a party run-aground on a sand bar. In nine years, the three day trip between these major colonial cities will take just two days one way or five days round trip, with a day in Philadelphia for business. New accommodations include larger stage-boats with more sail, known as periauguas or pirogues, and springs on the wagons to better cushion the bumps of poor road surfaces. (Stone, p186)

Likewise, an advertisement in The Pennsylvania Journal dated November 18, 1756, includes a mention of William Waller, mariner, out of Perth Amboy, operating a sloop as a "commodious" passenger-carrying "stage-boat" to New York and back. (NJ Archives s1 v20 p78-79)

Philadelphia and Perth-Amboy Stages.

Notice is hereby given, that we the Subscribers, John Butler, of Philadelphia, at the Sign of the Death of the Fox, in Strawberry Alley, begins his Stage on Tuesday, the Ninth of this Instant November, from his House and will proceed with his Waggon to the House of Nathaniel Parker, at Trenton Ferry; and from there the Goods and passengers to be carried over the ferry to the House kept by George Moschel, where Francis Holman will meet the above John Butler, and exchange their passengers, &c. and then proceed on Wednesday through Princetown and New-Brunswick, to the House of Obadiah Airies, in Perth-Amboy, where will be kept a good Boat, with all Conveniences necessary, kept by John Thomson and William Waller, for the Reception of passengers, &c. who will proceed on Thursday Morning, without Delay, for New York, and there land at Whitehall, where the said Waller and Thompson will give Attendance at the House of Abraham Bockeys, until Monday Morning following, and then will return to Perth Amboy, where Francis Holman on Tuesday Morning following will attend, and return with his Wagon to Trenton Ferry, to meet John Butler, of Phildelphia, and there exchange their Passengers, &c. for New-York and Phildelphia.

It is hoped, that as these Stages are attended with a considerable Expence, for the better accommodating Passengers, that they will merit the favours of the Publick; and whoever will be pleased to favour them, with their Custom, shall be kindly used, and have due Attendance given them by their humble Servants John Butler, Francis Holman, John Thompson, and William Waller.

Stone's History of New York City includes the following description of this early New York to Philadelphia stage route. (Stone, p186)

Another route advertised a commodious 'stage-boat' to start with goods and passengers from the City Hall Slip (Coenties) twice a week, for Perth Amboy ferry, and thence by stage-wagon to Cranberry and Burlington, from which point a stage-boat continued the line to Philadelphia; this trip generally required three days. This was long before the days of steam-boats. These 'stage-boats' were small sloops, sailed by a single man and boy, or two men; and passing 'outside,' as it is still called, by the Narrows and through the 'Lower Bay,' these small passage-vessels, at times, were driven out to sea, thus oftentimes causing vexatious delays. In very stormy weather, the 'inside route,' through the Kills, was chosen. The most common way to Philadelphia, however, was to cross the North River in a sail-boat, and then the Passaic and Hackensack by scows, reaching the 'Quaker City' by stages in about three days. But these passages had their perils.

I find no further public accounts of Captain Samuel FitzRandolph, his sons, Samuel and Kinsey, or the rest of the crew. "Of Captain Zebulon Wade, he was known to have moved from his native Scituate to 'Carolina,' where his son later was found to be a ship’s pilot on the North Carolina Rivers . . ." (Wadsworth)

Piracy continues to be a concern of the royal government. A circular letter dated May 20, 1757, Whitehall, from the Secretary of State to the Governors in North America addresses further piracy with this missive: "In consequence of some of the privateers being guilty of piracy, the Governors are directed to arrest them should they touch any of the ports, and that every privateer be furnished with a copy of instructions as to their conduct at sea." That is all. (NJ Archives v10, p340)

On June 21, 1757, the original subject of this research, 21 year old Joseph (Thorne) Jackson of Woodbridge, mariner, dies. The cause of such a premature death is not reported. His estate is administered by relatives and Friends Abraham Shotwell and Abraham Smith. It appears that he never marries, has no children, and accumulates no estate of value. (NJ Archives v32, p174)

The lost cargo of the ill-fated armada of August 1750 is yet of interest to some treasure hunters. Two hundred fifty years after that fateful storm subsides, a legal tempest brews over dividing up the booty, according to goinglegal.com. The International Registry of Sunken Ships summarizes the case as follows.

In 1998, Sea Hunt obtained permits from the Virginia Marine Resources Commission to explore for submersed vessels along the Virginia Coast. After spending nearly a million dollars in its search, Sea Hunt revealed that it had located the sunken remains of JUNO and LA GALGA. In order to resolve title to the shipwrecks, Sea Hunt sought a declaratory judgment from the district court stating that Virginia, rather than Spain, owned the vessels. The United States, fearing that the judgment would persuade other nations to divest its similarly situated shipwrecks, filed a claim on Spain's behalf asserting ownership over the vessels. The district court rejected the United States' efforts, but permitted Spain to file its own verified claim. Then, the district court, applying an express abandonment standard, held that Spain retained ownership over JUNO, but had expressly abandoned LA GALGA through Article XX of the 1763 Definitive Treaty of Peace between France, Great Britain and Spain.

As for the pirated pieces-of-eight and "Treasure Island," Wadsworth reports that “the Spanyards had ploughed and dug the island near all over and had found probably the most of it.” Knight concludes for us it "was estimated by a British Court that investigated this case that the total value of the cargo stolen from the Nuestra Señora de Guadeloupe exceeded 250,000 Spanish dollars. Of the 150,000 pieces-of-eight said to have been buried on Norman Island by Owen Lloyd and his crew, some 57,000 have never been accounted for."

Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, Volume 10, New Jersey Historical Society, 1858.

Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey v.7, New Jersey Archives s.1, 1883.

Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey v.10, New Jersey Archives s.1, 1886.

Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey v.12, New Jersey Archives s.1, 1895.

Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey v.16, New Jersey Archives s.1, 1891.

Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey v.19, New Jersey Archives s.1, 1897.

Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey v.20, New Jersey Archives v.1, 1898.

Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey v.22, New Jersey Archives s.1, 1900.

Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey v.30, New Jersey Archives s.1, 1918.

Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey v.32, New Jersey Archives v.1, 1924.

Encyclopedia Brittanica Online, Encyclopaedia Brittanica, Inc., 2010.

Genealogical and Family History of the State of Maine, v.3, Henry Sweetser Burrage and Albert Roscoe Stubbs, 1909.

History of New York, William Leete Stone, 1872.

History of Seafaring Piracy Found in Archives, David Wadsworth, Cohasset Mariner, 1988.

International Registry of Sunken Ships by

Ocracokers, Alton Ballance, 1989.

Pieces of Eight, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2010.

Pirates 'Brethren of the Seas', Oracle Education Foundation, ThinkQuest : Library, 2001.

Report concerning the Spanish ship Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe landed in North Carolina by Gabriel Johnston and Juan Manuel de Bonilla, 1750, as reprinted in

Documenting the American South Colonial and State Records of North Carolina by the University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2004-2010.

Shipwrecks and Treasure: the Spanish Treasure Fleet of 1750, Peter Bilton, Factóidz, 2010.

Shipwrecks, Sea Raiders, and Maritime Disasters along the Delmarva Coast 1632-2004 , Donald Shomette, 2007.

The Colonial Records Project, Jan-Michael Poff, Editor, 2010.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica, Ninth Edition, Volume 5, Thomas Spencer Baynes, 1833.

The Outer Banks of North Carolina, 1584-1958, David Stick and Frank Stick, 1958.

The Roll Family Windmill, William Henry Roll, 2010.

The Story of the Norman Island Treasure, Gerald Singer, 2008.

Zebulon Wade, Pirate or Privateer?, Richard H. Benson, American Ancestors, Spring 2010.